King Lear

An Introduction

By Dennis Abrams

————————————

We are now, I think, at the peak of Mount Shakespeare. King Lear has long had a reputation as the ultimate in tragedy – this tale of a difficult father driven mad by the cruelty of his children asks more probing questions of its audiences that many commentators have felt equipped to provide. A.C. Bradley thought Lear was “Shakespeare’s greatest achievement’; William Hazlitt said that it was “the best of all Shakespeare’s plays’; G. Wilson Knight was so in awe of it that he spoke of ‘the Lear universe.’

We are now, I think, at the peak of Mount Shakespeare. King Lear has long had a reputation as the ultimate in tragedy – this tale of a difficult father driven mad by the cruelty of his children asks more probing questions of its audiences that many commentators have felt equipped to provide. A.C. Bradley thought Lear was “Shakespeare’s greatest achievement’; William Hazlitt said that it was “the best of all Shakespeare’s plays’; G. Wilson Knight was so in awe of it that he spoke of ‘the Lear universe.’

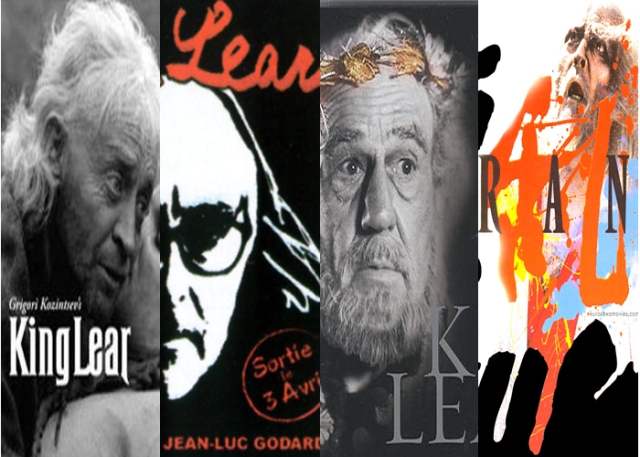

But on the other hand, many readers (and playgoers) have found the darkness, brutality, and sheer imaginative of this rawest of all tragedies way too much to handle – Tolstoy called it “unnatural,” (I’ll get more into Tolstoy and Lear later); Charles Lamb complained that “the Lear of Shakespeare cannot be acted,’ and even Bradley qualified his praise by saying that “it seems me to be not his best play” (at least in terms of theatrical performance). This overwhelming bleakness might explain why Shakespeare’s own version (or versions) of the play disappeared from the stage for nearly 200 years; replaced by a sentimental rewrite by Restoration dramatist Nahum Tate, who somehow managed to wrench a happy ending from the brutal wreckage of the original. Even so, today, three centuries after Tate, Lear seems more in tune with the pessimism and emptiness of our era than any other Shakespeare play: Jan Kott (who I will rely on heavily) completely changed the way we read the play by comparing it to Beckett and Ionesco’s theatre of the absurd, commenting that in Lear, ‘the abyss, into which one can jump, is everywhere,’ while emphasizing that “Lear, above all others, is the Shakespearean play of our time.”

DATE

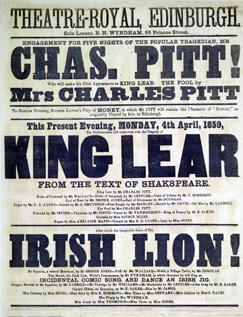

Probably written in 1605, although the first recorded performance of Lear took place on December 26, 1606, at the court of King James I.

SOURCES

Shakespeare’s most obvious source was an anonymous play performed by the Queen’s company, The Chronicle History of King Lear and His Three Daughters (not published until 1605). The Duke of Gloucester subplot is taken from Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, and some of Poor Tom’s language comes from a viciously anti-Catholic pamphlet (1603) by Anglican cleric Samuel Harsnett. Michel de Montaigne’s Essays also seem to have been fresh in Shakespeare’s mind at this point.

TEXTS

Here’s where it gets interesting. And complicated. Two distinct versions of the play exist. The first was printed in quarto in 1608; and seems to represent an early version; the 1623 First Folio includes a different text, seemingly revised by Shakespeare after performance. (There’s also a second quarto, published in 1619.)

For along time it was assumed that all three versions derived from a single lost authorial manuscript, and editors from the eighteenth century on cobbled them together as best they could. But it’s now thought that the Q texts were probably an early version of the play, with the Folio representing a revision made a few years later. The Folio loses around three hundred lines and adds another hundred, and because it is has more dramatic punch, it has been argued that these changes were made post-performance. Linguistic and stylistic tests support the belief that Shakespeare made the additions (as well as the cuts) so what these two sets of texts seem to offer is a rare insight into the ways he wrote and rewrote for the theater.

For our purposes, I’m going to be relying on the Pelican version (which is a conflation of quarto and folio), but if any of you would like to use a different version (the Oxford edition, includes both the quarto and folio texts), you’ll find it a fascinating experience.

As we work our way through the plays, I’ll try to cover differences in the texts when important.

———————

From Harold Bloom:

“King Lear, together with Hamlet, ultimately baffles commentary. Of all Shakespeare’s dramas, these show an apparent infinitude that perhaps transcends the limits of literature. King Lear and Hamlet, like the Yahwist’s text (the earliest in the Pentateuch) and the Gospel of Mark, announce the beginning and the end of human nature and destiny. That sounds rather inflated and yet merely is accurate; the Iliad, the Koran, Dante’s Comedy, Milton’s Paradise Lost are the only rival works in what still could be called Western tradition. That is to say that Hamlet and King Lear now constitute either a kind of secular scripture or a mythology, peculiar fates for two stage plays that almost always have been commercial successes.

“King Lear, together with Hamlet, ultimately baffles commentary. Of all Shakespeare’s dramas, these show an apparent infinitude that perhaps transcends the limits of literature. King Lear and Hamlet, like the Yahwist’s text (the earliest in the Pentateuch) and the Gospel of Mark, announce the beginning and the end of human nature and destiny. That sounds rather inflated and yet merely is accurate; the Iliad, the Koran, Dante’s Comedy, Milton’s Paradise Lost are the only rival works in what still could be called Western tradition. That is to say that Hamlet and King Lear now constitute either a kind of secular scripture or a mythology, peculiar fates for two stage plays that almost always have been commercial successes.

The experience of reading King Lear, in particular, is altogether uncanny. We are at once estranged and uncomfortably at home; for me, at least, no other solitary experience is at all like it. I emphasize reading, more than ever, because I have attended many stagings of King Lear, and invariably have regretting being there. Our directors and actors are defeated by this play, and I begin sadly to agree with Charles Lamb that we ought to keep rereading King Lear and avoid its staged travesties. That pits me against the scholarly criticism of our century, and against all the theater people that I know, but in this matter opposition is true friendship. In the pure good of theory, the part of Lear should be playable; if we cannot accomplish it, the flaw is in us, and in the authentic decline of our cognitive and literate culture. Assaulted by films, television, and computers, our inner and outer ears have difficulty apprehending Shakespeare’s hum of thoughts evaded in the mind. Since The Tragedy of King Lear well may be the height of literary experience, we cannot afford to lose our capability for confronting it. Lear’s torments are central to us, almost to all of us, since the sorrows of generational strife are necessarily universal.

Job’s sufferings have been suggested as the paradigm of Lear’s ordeal; I once gave credence to this critical commonplace, but now find it unpersuasive. Patient Job is actually not very patient, despite his theological reputation, and Lear is the pattern of all impatience, though he vows otherwise, and movingly urges patience on the blinded Gloucester. The pragmatic disproportion between Job’s afflictions and Lear’s is rather considerable, at least until Cordelia is murdered. I suspect that a different biblical model was in Shakespeare’s mind: King Solomon. I do not mean Solomon in all his glory – in Kings, Chronicles, and obliquely in the Song of Songs – but the aged monarch, at the end of his reign, wise yet exacerbated the supposed preacher of Ecclesiastes and of the Wisdom of Solomon in the Apocrypha, as well as the putative author of the Proverbs. Presumably Shakespeare was read aloud to from the Bishops Bible in his youth, and later read the Geneva Bible for himself in his maturity. Since he wrote King Lear as a servant of King James I, who had the reputation of being the wisest fool in Christendom, perhaps Shakespeare’s conception of Lear was influenced by James’s particular admiration for Solomon, wisest of kings. I admit that not many among us instantly associate Solomon and Lear, but there is crucial textual evidence that Shakespeare himself made the association, by having Lear allude to the following great passage in the Wisdom of Solomon, 7:1-6.

I myself am also mortal and a man like all other, and am come of

him that was first made of the earth.

And in my mother’s womb was I facioned to be flesh in ten moneths: I was broght together into blood of the sede of man, and by the pleasure that cometh with slepe.

And when I was borne, I received the comune air, and fel upon the earth, which is of like nature, crying & weeping at the first as all other do.

I was nourished in swaddling clothes, and with cares.

For there is no King that had any other beginning of birth.

All men then have no entrance unto life, and a like going out.

[Geneva Bible]

That is the unmistakable text echoed in Lear’s shattering sermon to Gloucester:

Lear:

If thou wilt weep my fortunes, take my eyes,

I know thee well enough, thy name is Gloucester,

Thou must be patient, we came crying hither:

Thou know’st the first time that we smell the air

We wawl and cry. I will preach to thee: mark.

[Lear takes off his crown of weeds and flowers.]

Gloucester:

Alack, alack the day!

Lear:

When we are born, we cry that we are come

To this great stage of fools.

(IV.vi.174-81)

After Solomon the kingdom was divided, as it was by Lear. Yet I don’t think that Shakespeare in part founds Lear upon the aged Solomon because of the catastrophes of kingdoms. Shakespeare sought we tend now not to emphasize in our accounts of Lear: a paradigm for greatness. These days, in teaching the play, I begin by insisting on Lear’s foregrounding in grandeur, because my students are unlikely at first to perceive it, patriarchal sublimity now being not much in fashion. Lear is at once father, king, and a kind of mortal god: he is the image of male authority, perhaps the ultimate representation of the Dead White European Male. Solomon reigned for fifty years, and was James I’s wished-for-archetype: glorious, wise, wealthy, even if Solomon’s passion for women was not exactly shared by the sexually ambiguous James. Lear is in no way a portrait of James, Shakespeare’s royal patron in all likelihood sympathized but did not empathize with the kingdom-dividing Lear. But Lear’s greatness would have mattered to James: he too considered himself every inch a king. I think he would have recognized in the aged Lear the aged Solomon, each in their eighties, each needing and wanting love, and each worthy of love.

When I teach King Lear, I have to begin by reminding my students that Lear, however unlovable in the first two acts, is very much loved by Cordelia, the Fool, Albany, Kent, Gloucester, and Edgar – that is to say, by every benign character in the play – just as he is hated and feared by Goneril, Regan, Cornwall, and Oswald, the play’s lesser villains. The play’s great villain, the superb and uncanny Edmund, is ice-cold, indifferent to Lear as he is even to his own father Gloucester, his half-brother Edgar, and his lovers Goneril and Regan. It is part of Shakespeare’s genius not to have Edmund and Lear address even a single word to each other in the entire play, because they are apocalyptic antitheses: the king is all feeling, and Edmund is bare of all affect. The crucial foregrounding of the play, if we are to understand it at all, is that Lear is lovable, loving, and greatly loved by anyone at all worthy of our own affection and approbation.”

———————————

From Mark Van Doren:

“’To judge of Shakespeare by Aristotle’s rules,’ said Pope,’ ‘is like trying a man by the laws of one country who acted under those of another.’ But if the truth about poetry is everywhere the same, and if Aristotle’s analysis of the art was sound, he will tell us as much about Shakespeare as he told us about Sophocles. He tells us a great deal about ‘King Lear’ when he remarks that tragedies have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The first scene of ‘King Lear’ is a beginning, but all the rest is end. The first scene of ‘King Lear’ is a beginning, but all the rest is end. The initial act of the hero is his only act; the remainder is passion. An old and weary king, hungry for rest, banishes the one daughter who would give it to him and plunges at once into the long, loud night of his catastrophe. An early recognition of his error does not save him. The poet does not wish to save him, for his instinct is to develop a catastrophe as none has been developed before or since. Henceforth King Lear is a man more acted against than active; the deeds of the tragedy are suffered rather than done; the relation of events is lyrical instead of logical, musical instead of moral. Such a play, if it is destined like this one to become the most tremendous of poems, must enrich itself with magnificent and immediate effects, with sensational tempest and intolerable tortures. It must incur the risk of seeming monstrous rather than terrible; it must have villains of enormous size – Edmund, Regan, Goneril – and it must give them the hearts of wolves. Edmund is Iago with a club and stilts, and Lear’s dog-hearted daughters, scowling with their thunder-brows, are like no other women in Shakespeare or the world. Such a lay must also, since it cannot order its events by intellect or law, deal heavily in sound. It must suggest, as “King Lear’ does, an analogy with the complexest imaginable music. ‘King Lear’ had to be a symphony to be anything at all; though only a giant’s genius could have built it into the symphony it is. It’s movement is not spearlike as ‘Hamlet’s’ is, a single curve of speed; it is glacial, inexorable, awful, and slow, pushing everything before it as its double front advances over Britain from west to east, from Lear’s island palace to the cliffs of Dover.”

“’To judge of Shakespeare by Aristotle’s rules,’ said Pope,’ ‘is like trying a man by the laws of one country who acted under those of another.’ But if the truth about poetry is everywhere the same, and if Aristotle’s analysis of the art was sound, he will tell us as much about Shakespeare as he told us about Sophocles. He tells us a great deal about ‘King Lear’ when he remarks that tragedies have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The first scene of ‘King Lear’ is a beginning, but all the rest is end. The first scene of ‘King Lear’ is a beginning, but all the rest is end. The initial act of the hero is his only act; the remainder is passion. An old and weary king, hungry for rest, banishes the one daughter who would give it to him and plunges at once into the long, loud night of his catastrophe. An early recognition of his error does not save him. The poet does not wish to save him, for his instinct is to develop a catastrophe as none has been developed before or since. Henceforth King Lear is a man more acted against than active; the deeds of the tragedy are suffered rather than done; the relation of events is lyrical instead of logical, musical instead of moral. Such a play, if it is destined like this one to become the most tremendous of poems, must enrich itself with magnificent and immediate effects, with sensational tempest and intolerable tortures. It must incur the risk of seeming monstrous rather than terrible; it must have villains of enormous size – Edmund, Regan, Goneril – and it must give them the hearts of wolves. Edmund is Iago with a club and stilts, and Lear’s dog-hearted daughters, scowling with their thunder-brows, are like no other women in Shakespeare or the world. Such a lay must also, since it cannot order its events by intellect or law, deal heavily in sound. It must suggest, as “King Lear’ does, an analogy with the complexest imaginable music. ‘King Lear’ had to be a symphony to be anything at all; though only a giant’s genius could have built it into the symphony it is. It’s movement is not spearlike as ‘Hamlet’s’ is, a single curve of speed; it is glacial, inexorable, awful, and slow, pushing everything before it as its double front advances over Britain from west to east, from Lear’s island palace to the cliffs of Dover.”

——————————–

From Frank Kermode:

“It is curious that this play, which it is surely impossible for anyone who cares about poetry to write on without some expression of awe, should offer few of the local excitements to be found, say, in the narrower context of Measure for Measure. The explanation must be that the subjects of King Lear reflect a much more general, indeed a universal tragedy. In King Lear we are no longer concerned with an ethical problem that, however agonizing, can be reduced to an issue of law or equity and discussed forensically. For King Lear is about suffering represented as a condition of the world as we inherit it or make it for ourselves. Suffering is the consequence of a human tendency to evil, as inflicted on the good by the bad; it can reduce humanity to a bestial condition, under an apparently indifferent heaven. It falls, insistently and without apparent regard for the justice they so often ask for, so often say they believe in, on the innocent; but nobody escapes. At the end the punishment or relief of death is indiscriminate. The few survivors, chastened by this knowledge, face a desolate future. The play demands that we think of its events in relation to the last judgment, the promised end itself, calling the conclusion an image of that horror. (V.iii.264-65).

“It is curious that this play, which it is surely impossible for anyone who cares about poetry to write on without some expression of awe, should offer few of the local excitements to be found, say, in the narrower context of Measure for Measure. The explanation must be that the subjects of King Lear reflect a much more general, indeed a universal tragedy. In King Lear we are no longer concerned with an ethical problem that, however agonizing, can be reduced to an issue of law or equity and discussed forensically. For King Lear is about suffering represented as a condition of the world as we inherit it or make it for ourselves. Suffering is the consequence of a human tendency to evil, as inflicted on the good by the bad; it can reduce humanity to a bestial condition, under an apparently indifferent heaven. It falls, insistently and without apparent regard for the justice they so often ask for, so often say they believe in, on the innocent; but nobody escapes. At the end the punishment or relief of death is indiscriminate. The few survivors, chastened by this knowledge, face a desolate future. The play demands that we think of its events in relation to the last judgment, the promised end itself, calling the conclusion an image of that horror. (V.iii.264-65).

Apocalypse is the image of human dealings in their extremity, an image of the state to which humanity can reduce itself. We are asked to imagine the Last Days, when, under the influence of some Antichrist, human beings will behave not as a rickety civility requires but naturally; that is, they will prey upon themselves like animals, having lost the protection of social restraint, now shown to be fragile. The holy cords, however ‘intrinse,’ can be loosened by rats. Gloucester may be credulous and venal, but his murmurings about the state of the world, which do not move Edmund, reflect the mood of the play: ‘in cities, mutinies; in countries; discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond crack’d ‘twist son and father…We have been the best of our time.’ (I.ii.107-12). The voices of the good are distorted by pain, those of the bad by the coarse excess of their wickedness.”

—————————-

From Stephen Booth:

“The tragedy of Lear, deservedly celebrated among the dramas of Shakespeare, is commonly regarded as his greatest achievement. I submit that King Lear is so because it is the greatest achievement of his audience, an audience of theatrically unaccommodated men. If an audience’s achievement in surviving the harrowing experience of King Lear could ever reasonably have been doubted, it has been taken for granted since this superbly forthright note on King Lear in Samuel Johnson’s edition of Shakespeare: ‘I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia’s death, that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.’ If my sensations could add anything to Johnson’s, I might relate that I myself first read the last scenes of King Lear while undergoing a sophomore survey course in which I was taking on a full semester’s reading in the last twenty-four hours immediately preceding the final examination; it was about three o’clock on a spring afternoon, and I sat in a chair in a stuffy library and cried. I had already read a pound and a half of certified masterpieces that day; I read as much before dawn; but with this one exception I was moved by nothing beyond the sophomoric ambition to become a junior. Further testimony to the singular power of the last scenes of King Lear is presumably unnecessary…”

“The tragedy of Lear, deservedly celebrated among the dramas of Shakespeare, is commonly regarded as his greatest achievement. I submit that King Lear is so because it is the greatest achievement of his audience, an audience of theatrically unaccommodated men. If an audience’s achievement in surviving the harrowing experience of King Lear could ever reasonably have been doubted, it has been taken for granted since this superbly forthright note on King Lear in Samuel Johnson’s edition of Shakespeare: ‘I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia’s death, that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.’ If my sensations could add anything to Johnson’s, I might relate that I myself first read the last scenes of King Lear while undergoing a sophomore survey course in which I was taking on a full semester’s reading in the last twenty-four hours immediately preceding the final examination; it was about three o’clock on a spring afternoon, and I sat in a chair in a stuffy library and cried. I had already read a pound and a half of certified masterpieces that day; I read as much before dawn; but with this one exception I was moved by nothing beyond the sophomoric ambition to become a junior. Further testimony to the singular power of the last scenes of King Lear is presumably unnecessary…”

—————————–

From G. Wilson Knight:

“It has been remarked that all the persons in King Lear are either very good or very bad. This is an overstatement, yet one which suggests a profound truth. In this essay I shall both expand and qualify it: the process will illuminate many human and natural qualities in the Lear universe and will tend to reveal its implicit philosophy.

“It has been remarked that all the persons in King Lear are either very good or very bad. This is an overstatement, yet one which suggests a profound truth. In this essay I shall both expand and qualify it: the process will illuminate many human and natural qualities in the Lear universe and will tend to reveal its implicit philosophy.

Apart from Lear, the protagonist, and Gloucester, his shadow, the subsidiary dramatic persons fall naturally into two parties, good and bad. First, we have Cordelia, France, Albany, Kent, the Fool, and Edgar. Second Goneril, Regan, Burgundy, Cornwall, Oswald, and Edmund. The exact balance is curious. It will scarcely be questioned that the first party tends to enlist, and the second to repel, our ethical sympathies in so far as ethical sympathies are here roused in us. But none are wholly good or bad, excepting perhaps Cordelia and Cornwall. Our imaginative sympathies, certainly, are divided: Albany is weak, Kent unmannerly, Edgar faultless but without virility, there is much to be said for Goneril and Regan, and Edmund is most attractive. There is no such violent contrast as the Iago-Desdemona antithesis in Othello. But the Lear persons are more frankly individualized than those in Macbeth; [My note: Bloom makes the same point as well.] though the Lear universe is created on a highly visionary plane, though all the dramatic persons are toned by its peculiar atmosphere, they are, as within that universe and as related to the dominant technique, clearly differentiated. King Lear gives one the impression of life’s abundance magnificently compressed into one play.

No Shakespearean work shows so wide a range of sympathetic creation: we seem to be confronted, not with certain men and women only, but with mankind. It is strange to find that we have been watching little more than a dozen people. King Lear is a tragic vision of humanity, in its complexity, in its interplay of purpose, its travailing evolution. The play is a microcosm of the human race – strange as that word ‘microcosm’ sounds for the vastness, the width and depth, the vague vistas which this play reveals. Just as skilful grouping on the stage deceives the eye, causing six men to suggest an army, grouping which points the eye from the stage toward the unactualized spaces beyond which imagination accepts in its acceptance of the stage itself, so the technique here – the vagueness of locality, and of time, the inconsistencies and impossibilities – all lend the persons and their acts some element of mystery and some suggestion of infinite purposes working themselves out before us. Something similar is apparent in Macbeth, a down-pressing, enveloping presence, mysterious and fearful: there it is purely evil, and its nature is personified in the Weird Sisters [MY NOTE: Unless you subscribe to Booth’s reading that the sisters are the true heroes of Macbeth.] Here it has no personal symbol, it is not evil, nor good; neither beautiful nor ugly. It is purely a brooding presence, vague, inscrutable, enigmatic; a misty blurring opacity stilly overhanging, interpenetrating plot and action. This mysterious accompaniment to the Lear story makes of its persons vague symbols of universal forces. But those persons, in relation to their setting, are not vague. They have outline, though few have colour: they are like near figures in a mist. They blend with the quality of the whole. The form of the individual is modified, in tone, by this blurring fog. The Lear mist drifts across them as each in turn voices its typical phraseology; for this impregnating reality is composed of a multiplicity of imaginative correspondencies in phrase, thought, action throughout the play. that mental atmosphere is as important, more important sometimes, than the persons themselves; nor, till we have clear sight of this peculiar Lear atmosphere, shall we appreciate the fecundity of human creation moving within it. King Lear is a work of philosophic vision. We watch, not ancient Britons, but humanity, not England, but the world. Mankind’s relation to the universe is its theme, and Edgar’s trumpet is as the universal judgment summoning vicious man to account. In Timon of Athens, the theme is universalized by the creation of a universal and idealized symbol of mankind’s aspiration, and the poet at every point subdues his creative power to a clarified, philosophic, working out of his theme. Here we seem to watch not a poet’s purpose, but life itself: life comprehensive, rich, varied. Therefore the clear demarcation of half the persons into fairly ‘good,’ and half into fairly ‘bad,’ is no chance here. It is an inevitable effect of a balanced, universalized vision of mankind’s activity on earth. But the vision is true only within the scope of its own horizon. That is, the vision is a tragic vision, the impregnating thought everywhere being concerned with cruelty, with suffering, with the relief which love and sympathy may bring, with the travailing process of creation and life. In Macbeth we experience Hall; in Antony and Cleopatra, Paradise; but this play is Purgatory. Its philosophy is continually purgatorial.”

And finally, from Garber:

“King Lear has often, and rightly, been regarded as a sublime account of the human condition. Words like ‘timeless’ and ‘universal,’ so often used as virtual synonyms for ‘Shakespeare,’ here find a fitting place. In the twentieth century in particular the celebrity of the play soared. [MY NOTE: Much more about this as we go on.] After the emergence of existentialism in philosophy, Lear’s ruminations on ‘being’ and ‘nothing’ seemed uncannily apt. The plays of Samuel Beckett – especially Endgame and Waiting for Godot – seemed to rewrite King Lear in a new idiom, and critical books like Maynard Mack’s ‘King Lear’ in Our Time and Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary, stressed the way the play voiced the despair and hope of a modern era. Yet this extraordinary play, in part a poignant and disaffected family drama, in part the political story of Britain’s union and disunion, bears as well explicit markers of the time in which it was written, and the time in which it was set. As we have seen with other Shakespeare plays that engage chronicle history, these three crucial time periods – the time the play depicts, the time of its composition, and the time in which it is performed or read – will always intersect.

“King Lear has often, and rightly, been regarded as a sublime account of the human condition. Words like ‘timeless’ and ‘universal,’ so often used as virtual synonyms for ‘Shakespeare,’ here find a fitting place. In the twentieth century in particular the celebrity of the play soared. [MY NOTE: Much more about this as we go on.] After the emergence of existentialism in philosophy, Lear’s ruminations on ‘being’ and ‘nothing’ seemed uncannily apt. The plays of Samuel Beckett – especially Endgame and Waiting for Godot – seemed to rewrite King Lear in a new idiom, and critical books like Maynard Mack’s ‘King Lear’ in Our Time and Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary, stressed the way the play voiced the despair and hope of a modern era. Yet this extraordinary play, in part a poignant and disaffected family drama, in part the political story of Britain’s union and disunion, bears as well explicit markers of the time in which it was written, and the time in which it was set. As we have seen with other Shakespeare plays that engage chronicle history, these three crucial time periods – the time the play depicts, the time of its composition, and the time in which it is performed or read – will always intersect.

That a play depicting the dismemberment of ancient Britain by the willful act of the old King Leir should have relevance to the stage of King James’s time is far from surprising. Shakespeare’s play was written around 1605, and in the period 1604-1607 James VI and I, King of Scotland and of England, was attempting to persuade Parliament to approve of the union of Scotland and England into one nation. It was James who first used the term ‘Great Britain’ to describe the unity of the Celtic and Saxon lands (England, Scotland, and Wales.) In his accession speech to Parliament on March 19, 1603, James had compared the union of Lancaster and York achieved by his ancestor Henry VII to the even more important ‘union of two ancient and famous kingdoms, which is the other inward peace annexed to my person.’ His language concerning civil and external war, and the remarkable metaphor of marriage and divorce that concludes this passage, are closely relevant to the dramatic action of King Lear. ‘Although outward peace be a great blessing,’ James wrote in ‘On the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England,’

‘yet is it far inferior to peace within, as civil wars are more cruel and unnatural than wars abroad. And therefore [a] great blessing that God has with my person sent unto you, is peace within, and that in a double form. First, by my descent, lineally out of the loins of Henry VII, is reunited and confirmed in me the union of the two princely roses of the two houses of Lancaster and York, whereof that King of happy memory was the first uniter, as he was also the first ground-layer of the other peace…

But the union of these two princely houses is nothing comparable to the union of two ancient and famous kingdoms, which is the other inward peace annexed to my person…Has not God first united these two kingdoms, both in language, religion, and similitude of manners? Yes, has he not made us all one island, compassed with one sea, and of itself by nature so indivisible, as almost those that were borderers themselves on the late borders, cannot distinguish nor know or discern their own limits? These two Countries being separated neither by sea, nor great river, mountain, nor other strength of nature…

And now in the end and fullness of time united, the right and title of both in my person, alike lineally descended of both the Crowns, whereby it is now become like a little world within itself, being entrenched and fortified round about with a natural, and yet admirable strong pond or ditch, whereby all the former fears of this nation are quite cut off. The other part of the island being ever before now, not only the place of landing to all strangers that were to make invasion here, but likewise moved by the enemies of the State, by untimely incursions, to make enforced diversions from their conquests, for defending themselves at home, and keeping sure their back door, as then it was called, which was the greatest hindrance and let that ever my predecessors of the nation had in disturbing them from their many famous and glorious conquests abroad. What God has conjoined then, let no man separate…’

In his speeches James regularly referred to the misfortunes that had brought disunion on early Britain – that is, the Britain of King Leir. James’s scheme of union would repair this ancient breach, correct this old mistake. Shakespeare’s play thus has a direct and pertinent topicality to the political issues of his day, a topicality few in his contemporary audiences could miss, although many viewers today will need to be reminded of this historical context. Likewise, the figure of Edgar, disguised as ‘Poor Tom,’ the madman, or ‘Bedlam beggar’ (from the Hospital of Saint Mary at Bethlehem in London that was used to house the insane), was an example of the kinds of ‘masterless men’ who roamed Britain’s towns and forests at this time, vagabond, often homeless and out of work, men whose very existence was viewed by the monarch as a threat to civil order and authority. Queen Elizabeth’s ‘Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion’ (1570), which she ordained to be proclaimed in the churches, had cautioned explicitly against the marauding of masterless men.

King Lear focuses at once on patriarchy and paternity, on the interaction between the role of the king and the role of the father. For Shakespeare’s time the idea of fatherhood was central to notions of governance, and the Bible taught, in the imagery of Saint Paul, that the structure of the family household should take the same form as the political structure. Thus the relationship of parents and children, fathers and daughters, and fathers and sons dominates the action. (We may notice that King Lear has no queen, nor the Duke of Gloucester a duchess.) For twentieth- and twenty-first-century readers and viewers living in nonmonarchial cultures, the notion of kingship may function as a metaphor, so that Lear is viewed primarily as a father, the head of a household, the father of daughters, his kingship receding into a notional world of fairy tale and nightmare.

One further prefatory observation is necessary before we turn to the plot and language of King Lear. As a result of textual investigations at the end of the twentieth century, many recent Shakespeare editors have concluded that there are two extant viable versions of the play. The History of King Lear, published in quarto form in 1608, which is considered to be the play as Shakespeare first wrote it, and The Tragedy of King Lear, published in the First Folio (1623) with revisions so substantial as to make it, in effect, a different play. Among the many differences between these versions are the presence in the Quarto of the mock trial scene in which the mad Lear rails at his ‘counselors,’ the Fool and ‘Poor Tom;’ the presence in the Quarto, only, of the ‘[s]unshine and rain at once’ passage; and the famous final lines, ‘We that are young…’ which are given to Edgar in the Folio and to Lear’s son-in-law Albany in the Quarto. In previous editions, until quite recently, editors followed a long-standing practice of blending the two texts, as is done with other plays where there are both quarto and folio versions, choosing the ‘best’ readings for each line and scene. Contemporary editorial decisions are more radical, in attempting to restore (or ‘un-edit’), the texts as they would have been known to readers and actors of Shakespeare’s time. The problem for modern readers and acting companies is that many people ‘know’ a version of Lear that, while it may not accord with the most advanced editorial decision making, nonetheless includes things that we are very reluctant to omit or change, however ‘impure’ the results from a scholarly perspective. In my observations on King Lear I will continue to include all scenes and passages that have become customarily associated with the play over the years, using the Folio as my primary source and indicating, when appropriate, for interested readers, when a scene appears only in the Quarto. My general philosophy about Shakespeare’s plays – as will already, I hope, be clear – is that they are living works of art that grow and change over time, not museum pieces that must only be preserved in some imagined state of purity (or petrification). Every production is an interpretation; world events and brilliant individual performances alike have shaped and changed these plays, so that they are ‘Shakespearean’ in their protean life, not restricted to some imagined (and unrecapturable) terrain of Shakespeare’s ‘intention’ or control. A final note on the Quarto/Folio question for Lear will underscore the issues with which I began, since the Quarto text calls itself a ‘history,’ and the Folio, a ‘tragedy.’ Plainly, as we have already seen, King Lear is both, and the elements of history intersect with the elements of tragedy to produce what the poet William Butler Yeats finely called an ‘emotion of multitude.’”

——————————–

Ready to start? You have no idea how excited I am to be reading Lear. And a head’s up – we’re really going to take our time with this one (if that’s OK with all of you) – I want to make sure to get this right.

Our next reading: King Lear, Act One

My next post: Tuesday evening/Wednesday morning

Enjoy.

Looking forward to this one too. Thanks for the great introduction!

Thanks Lesley!

As I drove into town I noticed that the whole world had a transcendent quality. A curtain had been pulled back and although I was driving around in my familiar life–this “glimpse”–had transformed everything! It took me awhile to connect the dots but I realized it was reading Lear that mornig which was having this resultant effect on my perceptions. Shakespeare has has transported (? what word to use?) through this tragedy, in a way very difficult to describe. Only one other time has the first encounter with a piece of art had such an immediate, yet not immediately recognizable, impact in my life. It is my hope through the course of this study to understand why such transcendence can result from such a god-awful, tragic story. What is Shakespeare revealing? Perhaps it is ‘the abyss, into which one can jump, is everywhere,’ (love this description!) I think I have jumped but rather than being a dark place ‘everywhere’, there is this luminosity which some might say is “genius”. I experience this spiritually something like the Buddhist “Heart Sutra”–form is emptiness, emptiness is form etc. etc. ending with GATE GATE PARA GATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SVAHA! (Gone, gone, gone beyond, hail the goer!)

This from Lear? How can it be?

Damn Lesley..>You don’t post often, but when you do…it’s a doozie. 🙂

I have a Pelican edition, but mine has both versions. I guess I’ll try to read both and compare?

Use the Folio as your main read if time is an issue, and I’ll try to talk about things that are only in one or the other as we go along.

I see the value of teaching King Lear to my AP students, and find the play a fascinating study of human drama. It transcends tragedy moving right into catastrophe. I look forward to your treatment as I feel I need more background on the play before my teaching confidence is at 100% ready. Which dramatization do you think best captures the play–Ian Holm or Patrick Stewart?

Cricket: I’m not sure yet — I’ll get back to you when we’ve finished the play…:-)

The Pelican Edition has 3 versions…the Quarto and Folio texts as well as a ‘Conflated Text’ … is the latter unique to the Pelican edition or has it become the ‘standard’ text in education/academia?

And for the purposes of this blog, which is the best to follow? (a bit confused – sorry!)

I’m going to be using the “conflated text” — if you read Garber’s take on this at the end of my post, I think that makes the most sense.

I just discovered this site today but I look forward to going on with you and catching up with past discussions. By way of background, I consider myself an enthusiastic fan, having watched dozens of live and filmed Shakespeare plays and even performed in three (Twelfth Night and two versions of Midsummer, one of which opens tomorrow night). I had the chance to visit Stratford last year and saw an original 1619 quarto of Lear and Tate’s rewrite, just sitting on the table in front of me.

Joe: Glad to have you with us! Dennis

Good post. I learn something more difficult on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content business writers and employ a little something at their store. I�d prefer to use some with the articles on my website whether a person don�t mind. Natually I�ll give you a link on your own web blog. Appreciate your sharing.

aaron http://www.nexopia.com/users/state30parade/blog/1-ideas-on-how-to-face-kidney-impaired-function-before-time-expires