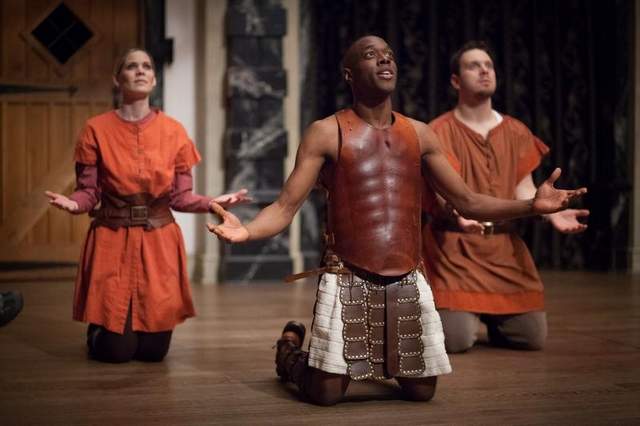

The Two Noble Kinsmen

Act Four

By Dennis Abrams

Act Four: The Jailer’s Daughter, now completely mad, is reunited with her father. Observing her behavior, the Doctor advises that the only possible remedy is if a former suitor (the Wooer) simply pretends that he is Palamon. In the meantime, Emilia is still unable to choose between her two suitors – so the contest between the two rivals must proceed.

Act Four: The Jailer’s Daughter, now completely mad, is reunited with her father. Observing her behavior, the Doctor advises that the only possible remedy is if a former suitor (the Wooer) simply pretends that he is Palamon. In the meantime, Emilia is still unable to choose between her two suitors – so the contest between the two rivals must proceed.

The plight of the Jailer’s Daughter, in loving someone socially beyond her reach, is rather unusual in Shakespeare (Helen in All’s Well is her closest relative) – Shakespeare’s women seem to marry beneath them – unusual enough for the Restoration dramatist William Davenant to enhance his status in his adaptation so that she can marry Palamon after all. (Davenant called his adaptation The Rivals. As with his other reworkings of Shakespeare’s plays, this bulldozed many of the play’s more unsettling aspects and turned it into a straight comedy. Arcite is spared death while “Celania” (equivalent to the Jailer’s Daughter in the original play) is magically cured and married to “Philander,’.)

But The Two Noble Kinsmen does not permit itself such a tidy conclusion, and in this play, the remainder of the daughter’s experience is fairly wretched. A doctor persuades her father that the best cure for her illness is simply for the man who was wooing her previously (the script just calls him “Wooer”) to seize advantage of her mental imbalance. “Take upon you, young sir,” he tells the Wooer,

the name of Palamon; say you come to eat with her, and to commune of love. This will catch her attention, for this her mind beats upon…Sing to her such green songs of love as she says Palamon hath sung in prison; come to her stuck in as sweet flowers as the season is mistress of, and thereto make an addition of some other compounded odours which are grateful to the sense. All of this shall become Palamon, for Palamon can sing, and Palamon is sweet and ev’ry good thing.

(4.3.72-84)

“It is a falsehood she is in,” the Doctor smartly concludes, “which is with falsehoods to be combated” (4.3.90-1), and many real-life Renaissance physicians would probably have agreed with his treatment. Even so, the tone of the play is, I think, difficult here to read, balanced between comedy and something incalculably more perplexed – as it was a few scenes earlier, when the Daughter happened upon a group of country folk who took advantage of her insanity by getting her to join their chorus line and perform for Duke Theseus. While the rustic performance is of course another nod to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the suggestion in Kinsmen that it doesn’t really matter whom the Daughter loves, Palamon or another man pretending to be him, also plays some of the Dream’s comedy concerns, but in a much darker key.

A little earlier the Jailer’s Daughter is reported as having attempted to drown herself: death is a nagging theme in the play. Having opened on a scene in which three widowed queens plead with Theseus for their slaughtered husbands to be given a decent burial, the play has a finale, which resolves the conflict between Palamon and Arcite only in the messiest of ways, that is equally gruesome. Finding the two kinsmen fighting illegally in the woods, Theseus decides that unless Emilia can decide between them, they must face each other in combat one last time, with whoever losing facing execution. In what is probably a nod to the masques increasingly popular with the King’s Men’s royal employer, this climactic contest – like the queen’s formal appeals to Theseus – will be performed with plenty of courtly, pseudo-medieval trappings. Each combatant is attended by three knights, and Theseus orders that whoever succeeds in touching a pyramid he sets up (an ancient symbol of success) will win the lady’s hand. Yet, at the heart of these intricate performances like a stark emotional crisis. Emilia has no answer to the quandary she faces, and in a later scene she is movingly depicted debating which of the two men is better (she ultimately can’t decide – and how can she? They’re basically the same.) Earlier Arcite had declared with characteristic fervor that to be removed from her sight would be ‘death/Beyond imagination’ (2.3.4-5), but here the risk he and Palamon face is painfully real: Emilia’s inability to choose between her suitors guaranteed that one of them must die.

From Garber:

“One of the play’s many pleasures is the way it juxtaposes the ‘high’ courtly and triangulated romance of Palamon, Arcite, and Emilia with the ‘low’ story of the Jailer’s Daughter and her Wooer. The fact that these country characters have labels rather than names – not unusual in plays of the period – underscores their difference from the nobility. Yet the Jailer’s Daughter, and indeed the Jailer himself, are in some ways far more vivid characters than their courtly counterparts. The Daughter falls in love with Palamon after at least slightly more acquaintance than the noble kinsmen have with Emilia, and Emilia, for her part, reenacts that scene of falling-in-love-from-afar in a comical replay in act 4, after she has told them both to forget her and then agreed to marry whichever wins the contest. ‘Enter Emilia with two pictures,’ says the stage direction, and the lady proceeds to admire first one, then the other, than the first again. ‘What a sweet face has Arcite!’ she rhapsodizes (4.2.7). ‘Palamon/is but his foil’ (25-26). And then, ‘I have lied so lewdly/…On my knees/I ask thy pardon, Palamon, thou art alone/And only beautiful’ (4.2.35-38). ‘Lie there, Arcite,’ she says, putting down his picture. ‘Thou art a changeling to him, a mere gypsy,/And this the noble body. I am sotted,/Utterly lost’ (4.2.43-46). Ultimately she confesses to herself that she is unable to choose. ‘What a mere child is fancy,/That, having two fair gauds of equal sweetness,/Cannot distinguish, but must cry for both!’ (4.2.52-54).

“One of the play’s many pleasures is the way it juxtaposes the ‘high’ courtly and triangulated romance of Palamon, Arcite, and Emilia with the ‘low’ story of the Jailer’s Daughter and her Wooer. The fact that these country characters have labels rather than names – not unusual in plays of the period – underscores their difference from the nobility. Yet the Jailer’s Daughter, and indeed the Jailer himself, are in some ways far more vivid characters than their courtly counterparts. The Daughter falls in love with Palamon after at least slightly more acquaintance than the noble kinsmen have with Emilia, and Emilia, for her part, reenacts that scene of falling-in-love-from-afar in a comical replay in act 4, after she has told them both to forget her and then agreed to marry whichever wins the contest. ‘Enter Emilia with two pictures,’ says the stage direction, and the lady proceeds to admire first one, then the other, than the first again. ‘What a sweet face has Arcite!’ she rhapsodizes (4.2.7). ‘Palamon/is but his foil’ (25-26). And then, ‘I have lied so lewdly/…On my knees/I ask thy pardon, Palamon, thou art alone/And only beautiful’ (4.2.35-38). ‘Lie there, Arcite,’ she says, putting down his picture. ‘Thou art a changeling to him, a mere gypsy,/And this the noble body. I am sotted,/Utterly lost’ (4.2.43-46). Ultimately she confesses to herself that she is unable to choose. ‘What a mere child is fancy,/That, having two fair gauds of equal sweetness,/Cannot distinguish, but must cry for both!’ (4.2.52-54).

Emilia’s dialogue with the two pictures (presumably miniatures, of the soft often given as love tokens) will remind a modern Shakespeare audience of the more famous scene in Hamlet, where Hamlet challenges his mother to see the dissimilarity between her two husbands, old Hamlet and Claudius, who are also, technically, ‘noble kinsmen’ (‘Look here upon this picture, and on this,/The counterfeit presentment of two brothers’ [Hamlet 3.4.52-53]). The stage echo of Hamlet is given more pertinence by the fact that in the previous scene (4.1) we hear of the madness of the Jailer’s Daughter, presented, like that of Ophelia, in a long set piece, an ‘unscene’ narrating events that have taken place offstage and out of our sight. The lovesick girl is described as singing songs – including Desdemona’s ‘Willow, willow, willow’ — unbinding her hair (loose hair was a classic stage sign of madness in women), plucking flowers, and speaking aimlessly of her father’s death and burial. But the Daughter will live to marry her faithful Wooer (in his therapeutic disguise as “Palamon’), and the Jailer will not meet Polonius’s ignominious end. Like many of the last plays in which Shakespeare had a hand, and especially his late romances, this play seems to cite, quote, and excerpt from key moments in earlier Shakespearean plays, especially those that were – and are – memorable onstage. And as was the case in those late other plays, the citation (for example, Leontes’ jealousy of Hermione, compared with Othello’s jealousy of Desdemona) is briefer, less motivated, and slightly more distanced from character and personality than its tragic original. It has, in short, become a trope, a figure in this case not so much ‘of speech’ as ‘of stage,’ recognizable as a Shakespearean minigenre.”

And from Frank Kermode:

“The Two Noble Kinsmen breaks the association of Shakespeare with the original Globe Theatre; it may have been performed in the new one, opened in June 1614, but it was probably performed at the Blackfriars. It must have been liked, since it was known to have been played in 1619, and the Quarto edition was published as late as 1634. As with Henry VIII, the question of authorship and shares remains contested, but it seems that in general Shakespeare is to be credited with Act I and the first scene of Acts II, III, and V, and the last two scenes.

“The Two Noble Kinsmen breaks the association of Shakespeare with the original Globe Theatre; it may have been performed in the new one, opened in June 1614, but it was probably performed at the Blackfriars. It must have been liked, since it was known to have been played in 1619, and the Quarto edition was published as late as 1634. As with Henry VIII, the question of authorship and shares remains contested, but it seems that in general Shakespeare is to be credited with Act I and the first scene of Acts II, III, and V, and the last two scenes.

Charles Lamb may have overstated the contrasts, but his comparison between the manner of Fletcher and that of Shakespeare has some justice: ‘[Fletcher’s] ideas move slow; his versification, though sweet, is tedious, it stops every moment; he lays line upon line, making up one after the other, adding image to image so deliberately that we see where they join: Shakespeare mingles everything, he runs line into line, embarrasses sentences and metaphors; before one idea has burst its shell, another is hatched out and clamorous for disclosure.’

The terms of the comparison may be too favorable to Shakespeare: The Two Noble Kinsmen is a romance, light in texture and sometimes rather silly, and the style preferred by Lamb seems unsuited to it. A recent editor suggests that at this stage of his working life, almost at its end, Shakespeare was somewhat under the influence of Donne, who had the habit, as Coleridge put it, of wreathing iron pokers into true love knots. It has been argued, defensively, that ‘the age often found in incomprehensibility a positive virtue.’ But Donne was not writing for a theatre audience.

The speeches of the Three Queens at the beginning of the play have a right to be impassioned, as they communicate their desire to buy their husbands, but they tend to be complicated in expression:

O, my petition was

Set down in ice, which by hot grief uncandied

Melts into drops; so sorrow wanting form

Is press’d with deeper matter.

(I.i.106-9)

She means that in her earlier plea she had spoken too coldly; now her grief has melted the ice and she weeps. So far so good; Shakespeare more than once thought of ice as candy, as we have seen in Antony and Cleopatra. But what follows is very obscure and, if puzzled out, adds little to the sentiment; it seems to offer the generalization that sorrow is harder to bear if it cannot find a form of expression. This Third Queen is particularly hard to understand:

There, through my tears,

Like wrinkled pebbles in a glassy stream,

You may behold’em, Lady, lady, alack!

He that will all the treasure know o’ th’ earth

Must know the centre too; he that will fish

For my least minnow, let him lead his line

To catch one at my heart.

(111017)

What are to be beheld are presumably ‘eyes’; but ‘’em’ has no plural antecedent. The remainder of the statement is presumably meant to suggest the depth of her grief by comparing it to the centre of the earth, and by saying that to fish for it you would need to weight the line. There are more examples of unprofitable complexity in this play. here Arcite addresses his friend and enemy Palamon in V.i:

I am in labor.

To push your name, your ancient love, our kindred,

Out of my memory; and i’ th’ self-same place

To eat something I would confound. So hoist we

The sails that must these vessels port even where

The heavenly limiter pleases.

The verb ‘port’ and the noun ‘limiter’ give the expression of this perfectly understandable idea connotations more obscure and mysterious than its occasion seems to require. The general idea is expressed by a confusion of the figure of labour pains, the figure of ships sailing in different directions, and the idea that he wants to put in the place of his friend Palamon an enemy of the same name. But even this last notion is not clear, for he presumably does not want the enemy only in his memory.

Arcite’s speech to his knights (V.i.34ff.) contains lines that have baffled commentators, lines of which an audience would deserve congratulations if they caught the general drift. Some compensation may be found in the fineness of his address to Mars, with its odd reminiscence of Macbeth:

Thou might one, that with thy power hast turn’d

Green Neptune into purple, [whose approach]

Comets prewarn, whose havoc in vast field

Unearthed skulls proclaim, whose breath blows down

The teeming Ceres’ foison, who dost pluck

With hand armipotent from forth blue clouds

The mason’d turrets, that both mak’st and break’st

The stony girths of cities: me thy pupil,

Youngest follower of thy drum, instruct this day

With military skill, that to thy laud

I may advance my streamer, and by thee

Be styl’d the lord o’th’ day.

(V.i.49-60)

The incantatory, almost liturgical purpose of the speech limits the scope of involution; there is no doubling back, but a cumulative celebration of the destructive power of war; the battlefields are strewn with unburied corpses, the ruined harvests, the cities besieged and destroyed; and finally there is apt petition for ‘military skill,’ and the dedication of success to the praise of the god. The strange words – ‘armipotent,’ ‘laud,’ and ‘streamer’ [pennon] – are all slightly out of the common way yet within reasonable intellectual compass; ‘the lord o’th’ day’ gives the sense to a festive combat or tourney, which, despite its homicidal purpose, this joust amounts to. The passage is indebted to Arcite’s prayer to Mars in Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale, but, it is grander and has its own rapt quality.

Since she is the sister of the military Hippolyta, Emilia, for the fight between the kinsmen is perhaps entitled on occasion to speak with the masculine persuasive force of Shakespeare:

Half-sights saw

That Arcite was no babe. God’s lid, his richness

And costliness of spirit look’d through him, it could

No more be hid in him than fire in flax,

Than humble banks can go to law with waters

That drift-winds force to raging.

(V.iii.95-100)

Emilia’s oath ‘God’s [eye]lid’) has surprised the commentators, and might seem to fall under the ban of the Act of 1606, but the terms in which she praises Arcite are even more striking. ‘Costliness,’ a redundant reinforcement to ‘richness,’ is odd, as it applies to his spirit, not his fine dueling clothes; the notion of a fine spirit looking through a person’s body is now more familiar from some familiar lines of Donne, written and published at just this time. (We understood/Her by her sight; her pure and eloquent blood/Spoke in her cheeks, and so distinctly wrought/That one might almost say, her body thought.’ Of the Progress of the Soul, 1612) Emilia, having expressed this idea, finds two similes to reinforce it: the fire in the flax and, more remote, the impossibility that riverbanks can go to law against flood ties. This last comparison is bizarre enough without the added difficulty that the rush of water is due to ‘drift winds.’ Editors plausibly guess that the word ‘drift’ means ‘driving’; indeed, it is hard to see what else it could mean, but the usage is apparently unique; and considering Shakespeare’s ease in converting nouns to verbs, it may be worth while occasionally to consider that the effect, though undoubtedly striking and ‘muscular,’ is sometimes merely distracting. ‘Waters/That drift winds force to raging’ might be defended on the ground that the language itself is being driven and forced, in imitation of flood water in spate; but in the end the inability of the banks to do anything about it has hardly any relation to the original idea, that Arcite’s noble spirit ‘look’d through him.’

Sometimes it seems that Shakespeare, in these latter years, is simply defying his audience, not caring to have them as fellows in understanding. One finds editors reduced to saying, ‘The idea is clear…but it is hard to make grammatical sense out of the lines.’ It is a price we have to pay. Consider this:

Here we are,

And here the graces of our youths must wither

Like a two-timely spring. Here age must find us,

And which is heaviest, Palamon, unmarried.

The sweet embraces of a loving wife,

Loaden with kisses, arm’d with thousand Cupids,

Shall never clasp our necks; no issue know us;

No figures of ourselves shall we ev’r see

To glad our age, and like young eagles teach ‘em

Boldly top gaze against bright arms, and say,

‘Remember what your fathers were, and conquer!’

(II.ii.26-36)

This is the soft, explicit Fletcher, admirably skilled with his dying falls and his willingness to spell everything out. Presumably the managers of the King’s Men could have made him a collaborator with Shakespeare, fifteen years his senior, and the author who, for fifteen years, had so astonishingly enlarged the drama and educated its audience. It must have been a strenuous experience for everybody involved. But now those who could afford it might relax at the Blackfriars to the tunes of Fletcher. Shakespeare sounds still as if the work of transformation was not done, that the testing of the audience (and himself) must go on. Did he overestimate their endurance, and ours; did he perhaps even exaggerate his own?”

Our next reading: Act Five of The Two Noble Kinsmen

My next post: Sunday evening/Monday morning. And, after that, I’ll have posts (two or three, I’m not sure yet) summing everything up.

Enjoy. And enjoy your weekend.