King Lear

Act One, Part One

By Dennis Abrams

———————–

King Lear of Britain

Goneril, Lear’s oldest daughter

Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband

Regan, Lear’s second daughter

Duke of Cornwall, Regan’s husband

Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter

Duke of Burgundy, Cordelia’s first suitor

King of France, Cordelia’s second suitor

Earl of Kent, a follower of Lear (later disguised as Caius, a servant of the King)

Earl of Gloucester

Edgar, Gloucester’s legitimate son, and his eldest (later disguised as “Poor Tom”)

Edmund, Gloucester’s illegitimate and younger son

Old Man, a servant of Gloucester

Curan, a courtier

Fool in Lear’s service

Oswald, Goneril’s steward

——————————————————

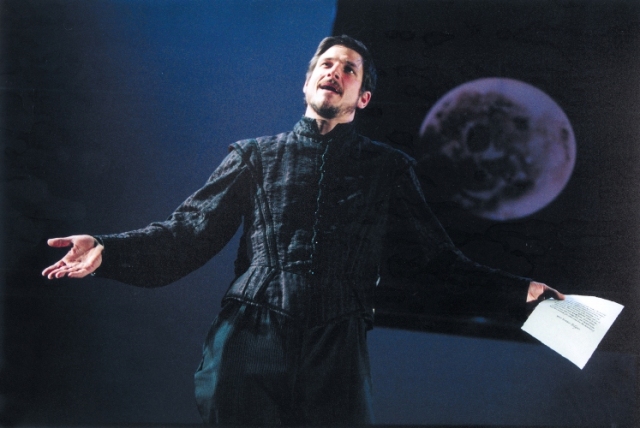

Act One: King Lear wishes to divide his kingdom among his three daughters, according to whoever loves him most. Goneril and Regan speak sycophantically (kiss his ass to put it bluntly) and are rewarded, but his younger (and favorite) daughter Cordelia refuses to flatter him. Angered by her response, Lear rejects her and gives her share to her sisters – with whom he now intends to spend his time now that he’s “retired.” Despite Cordelia’s loss of royal favor, the King of France agrees to marry her, but when Kent tries to defend her, Lear banishes him. Meanwhile, Gloucester’s illegitimate son Edmund is planning to frame his brother Edgar and steal his land; he shows Gloucester a forged letter supposedly revealing Edgar’s plans to kill him. At Goneril’s castle, the new domestic arrangements, are, not surprisingly, not working: Lear and what remains of his retinue are accused of being too rowdy, so he departs in a rage for Regan’s palace, along with the Fool and a disguised Kent.

Act One: King Lear wishes to divide his kingdom among his three daughters, according to whoever loves him most. Goneril and Regan speak sycophantically (kiss his ass to put it bluntly) and are rewarded, but his younger (and favorite) daughter Cordelia refuses to flatter him. Angered by her response, Lear rejects her and gives her share to her sisters – with whom he now intends to spend his time now that he’s “retired.” Despite Cordelia’s loss of royal favor, the King of France agrees to marry her, but when Kent tries to defend her, Lear banishes him. Meanwhile, Gloucester’s illegitimate son Edmund is planning to frame his brother Edgar and steal his land; he shows Gloucester a forged letter supposedly revealing Edgar’s plans to kill him. At Goneril’s castle, the new domestic arrangements, are, not surprisingly, not working: Lear and what remains of his retinue are accused of being too rowdy, so he departs in a rage for Regan’s palace, along with the Fool and a disguised Kent.

——

If you look at it one way, King Lear is all about politics. It begins with a ruler’s casual resignation from power, and ends in catastrophe when rival factions tear his company apart. And there’s good reason to think that the earliest audiences for this play – particularly on St. Stephen’s Night 1606 (December 26, the day after Christmas) when the audience for this new play included King James I, the king who had brought Scotland and England into a somewhat uneasy political union for the first time would have seen its relevance. Read as a warning to rulers, King Lear’s message is stark: power is yours, but so are the gravest of responsibilities. People’s lives, the lives of what the play calls the “poor naked wretches” who make up the commonwealth, matter. And it is only by being driven mad that King Lear realizes that truth, but one of the play’s man tragedies is this: by then it is too late, his kingdom has already vanished.

King Lear brings the political and the personal together, and it addresses not only politicians but ordinary mortals as well; it shows that who has power matters, and that problems afflicting a country’s rulers can have terrifying consequences. Shakespeare makes the story of what happens “when majesty falls to folly,’ as King Lear’s Kent so bluntly puts it, the epicenter of his tragedy. It famously opens with Lear’s declaration that it only by displaying “love” towards him (a love that has to find its way into polished words) that his daughters can be rewarded with political power, a share in the kingdom he is so recklessly and thoughtlessly breaking up. With the court crowded around, King Lear begins, “Tell me, my daughters –“

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state –

Which of you shall we say doth love us most,

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge?

Lear’s first mistake is to divide his realm; his second is to mix “love” with politics, and to completely misinterpret speeches describing love for the real thing. Two of his daughters, the devious Goneril and Regan, effortlessly perform as Lear requires, declaring their commitment “beyond what can be valued,” as Goneril describe it. But Lear’s third child, Cordelia is not prepared, and in fact is incapable of flattering her father, and her punishment is severe: her inheritance is cut off and she is left with no dowry with which to attract a husband.

The 40-year old Shakespeare, at this stage in his career a veteran of at least thirty major plans, probably found the skeletal story of Lear early in his career. It seems that he had links with an Elizabethan company who performed a play called The Chronicle History of King Leir and His Three Daughters in the early 1590s, when it seems likely that he was training as an actor. This old play is different from the new one in countless ways – Shakespeare cleaned up the plot and made innumerable changes – but it contains the story of a father and his daughters and the breakdown of the relationship between them, ingredients that the playwright would use to construct one of the most disturbing and shocking tragedies ever written.

——————————————————————————-

From Marjorie Garber:

“The play begins by instantiating a vision of social order. A trumpet is sounded, and a coronet is borne into the state chamber, and then there follows in order of rank and precedence, the powers of the state: King Lear, his sons-in-law, the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall; and his daughters in the order of their ages. (‘Albany’ is the ancient and literary name of Scotland; ‘Cornwall,’ of the southwest of England. Together these sons-in-law demarcate the Britain Lear is shortly to dismember.) Elaborate, ornate, imperial – as a madder and a wiser Lear will later declare, ‘Robes and furred gowns hide all’ – the scene before us is one of opulent magnificence and insistent order. It is a scene, above all, of ‘accommodated man,’ of humanity surrounded with wealth and power, robes and furs, warmth, food, and attendants – the radical opposite of the victim the play’s third act will supply, when Lear will tell the naked and tattered ‘Poor tom,’

“The play begins by instantiating a vision of social order. A trumpet is sounded, and a coronet is borne into the state chamber, and then there follows in order of rank and precedence, the powers of the state: King Lear, his sons-in-law, the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall; and his daughters in the order of their ages. (‘Albany’ is the ancient and literary name of Scotland; ‘Cornwall,’ of the southwest of England. Together these sons-in-law demarcate the Britain Lear is shortly to dismember.) Elaborate, ornate, imperial – as a madder and a wiser Lear will later declare, ‘Robes and furred gowns hide all’ – the scene before us is one of opulent magnificence and insistent order. It is a scene, above all, of ‘accommodated man,’ of humanity surrounded with wealth and power, robes and furs, warmth, food, and attendants – the radical opposite of the victim the play’s third act will supply, when Lear will tell the naked and tattered ‘Poor tom,’

[T]hou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art.

(3.4.96-97)

Unaccommodated man, and accommodated man. As the play begins the audience is confronted with kingly power in all its majesty, mankind apparently accommodated with everything it can imagine or desire. At the center of this world is the King. And yet, when the King begins to speak, we are at once made uneasy, if we are listening closely: ‘Meantime we shall express our darker purpose.’ In a play in which one of the central images will be sight and blindness, this is already a warning signal. What is the King’s darker purpose? Nothing less than the division of the kingdom, the willful creation of disorder:

Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom, and ‘tis our fast intent

To shake all cares and business from our age,

Conferring them on younger strength while we

Unburdened crawl toward death…

But this is contrary to everything that we know about kingship. It is clear not only from the precepts and practice of Elizabeth and James but also from very Shakespearean example that the ideal for rulers demands unity, not division, a single king, a strong ruler, and one who is prepared to choose a public life over a private one. Whether the king is Henry V or Julius Caesar, this principle holds; that the King should understand that the obligation is to hold together the state and unify its people. Yet here we have a king who intends to violate every single one of these proven precepts – who will attempt the physically and regally impossible, inviting his eldest daughters, ‘this crownet part between you, and who will also seek to escape the inescapable burden of morality ‘to ‘[u]unburdened crawl toward death,’ as if had regressed to the posture and position of a child.

Moreover, the entire scene has the quality of a fairy tale, and indeed of a well-rehearsed fairy tale: the king, the three daughters (two older and cruel, the youngest loyal, pure, and misunderstood) – there are no surprises here. We know and expect that the elder daughters will be wicked flatterers, the youngest their victim. Their joint business will be the division of the kingdom.

This is a purposeful fall, a fall by choice. The map is already present, the lands partitioned, awaiting the completion of the ritual as if the king has designed and planned it. Lear is testing what should need no test: the quality of nature and what is ‘natural.’ The whole play that follows will deal with this vexed question, of nature and of the ‘natural child.’ What is a natural child”? Is nature what Alfred, Lord Tennyson, would call ‘Nature, red in tooth and claw,’ the nature of pelican daughters, dog-hearted daughters, cannibals, and competitors? Or is nature a state akin to grace, a pattern of plentitude and order, like the lands the Lear of this opening scene has in his keeping: ‘With shadowy forests and with champaigns riched,/With plenteous rivers and wide-skirted meads.’ Nature as the kingly emblem of fertility, order, harvest, and grace. Which?

Lear:

Tell me, my daughters –

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state –

Which of you shall we say doth love us most,

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge?…

This is hubris, overweening pride, and presumptuousness, not only a violation of Lear’s responsibilities as King and man, but also a tempering with the bonds of nature, as his youngest daughter, Cordelia, well knows. And the replies of the two elder daughters, Goneril and Regan, to this love test have a rehearsed quality, a smooth deceptive flow. The whole scene is stylized and formal, until Cordelia breaks its frame. Goneril’s answer is apparently unequivocal:

Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter;

Dearer than eyesight, space, and liberty…

Eyesight, space, and liberty – all key themes in the play, all elements of which Lear and his fellow sufferer Gloucester will be bereft by the play’s end.

A love that makes breath poor and speech unable.

And Regan adds,

I am made of that self mettle as my sister,

And prize me at her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love –

Only she comes too short…

Notice ‘prize,’ ‘worth,’ ‘deed’ – all economic terms, which should alert us to the true nature of the elder daughter’s thoughts. Words, these sisters say, cannot express their feelings. ‘I am alone felicitate/In your dear highness’ love,’ Regan concludes.

Having expended words in saying that they have no words, the sisters receive their segments of the dismembered kingdom. Then it is Cordelia’s turn to speak:

Lear:

Now our joy,

Although our last and least…

……………………….

what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters? Speak.

Cordelia:

Nothing, my lord.

Lear:

Nothing?

Cordelia:

Lear:

Nothing will come from nothing. Speak again.

Cordelia:

Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth. I love your majesty

According to my bond, no more nor less.

Cordelia – whose name comes from the word for ‘heart’ (the Latin cor, cordis) – declares that she loves her father according to the bond of parent and child. This is the quintessence of the ‘natural.’ But Lear, whose language, like that of his elder daughters, has been sprinkled throughout the scene with legalisms, with cares and business, interest of territory, worth, deeds, and property, mistakes the natural for the unnatural, the bond of love for the bond of financial contract:

Cordelia – whose name comes from the word for ‘heart’ (the Latin cor, cordis) – declares that she loves her father according to the bond of parent and child. This is the quintessence of the ‘natural.’ But Lear, whose language, like that of his elder daughters, has been sprinkled throughout the scene with legalisms, with cares and business, interest of territory, worth, deeds, and property, mistakes the natural for the unnatural, the bond of love for the bond of financial contract:

Lear:

So young and so untender?

Cordelia:

So young, my lord, and true.

Lear:

Let it be so. Thy truth then be thy dower…

If love is measureable by ‘merit,’ by property and ‘wroth,’ then Cordelia’s natural claim of a bond begs no dowry, no reward. ‘H]er price is fallen, as Lear will shortly and bitterly tell her suitors. The inexpressible and immaterial is reduced to the merely material.

Like Desdemona before her, Cordelia gives voice to the choice of a husband over a father:

Why have my sisters husbands if they say

They love you all? Haply when I shall wed

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty.

Her word ‘plight’ here is typically rich deployment of Shakespearean word economy: a husband will take on the risk together with the betrothal, the ‘trothplight.’ Both words are from the same root, meaning ‘pledge’ or ‘danger.’ But Lear will not be moved: ‘Thy truth then be thy dower’ (‘Nothing will come of nothing.’). And, to the loyal supporter who would intervene: ‘Come not between the dragon and his wrath.’

In this opening scene, in Cordelia’s despairing counsel to herself – ‘What shall Cordelia speak? Love and be silent’ – we have the beginning of a highly significant dramatic and performative mode in Shakespeare, what might be called the rhetoric of silence. Some things cannot be said, cannot be given words. To abjure language in such cases is not a refusal of speech, like Iago’s final words, but rather an acknowledgment of the limitations of language, and the place of the ineffable or the unutterable. The modest and silent claim of a love according to her bond will distinguish Cordelia’s language, and her silence, throughout the play. Like Hamlet in the court of Claudius, dismayed by a falseness of ceremony and the role-playing all around him, Cordelia refuses to play the game, refuses to involve herself in playacting and willful deception. While Hamlet makes use of theatricality as a trap, Cordelia occupies what might be called the vanishing point of theatricality. We may think that Cordelia’s rigidity here is too pure a gesture, that she could bend, could compromise – but she, like her sisters, is her father’s daughter, stubborn and proud. Her motive in this moment seems plainly to disclaim artifice, to assert, again, something that in her understanding needs no assertion: the true and natural relationship between parent and child. But once disrupted, this ‘bond’ is not restored until tragedy has overtaken both Lear and Gloucester.

Cordelia’s rhetoric of silence will continue throughout the play, and will reach what is perhaps its most striking point when she herself becomes a condition of nature, at the point in act 4 (scene 17 in the Quarto text) when, beholding the ruined King, she will appear, in the words of an anonymous gentleman onlooker, like ‘[s]unshine and rain at once,’ split between smiles and tears, incapable of speech because of her love and pity. But we will also see the tragic limitations of her silence, the capacity of silence to be radically misunderstood, and the way in which Cordelia overcomes it and returns to speech.

At this point in the play, however, Cordelia’s silence is an antidote to the unfeeling hypocrisy of Goneril and Regan, the ‘glib and oily art’ of their glozing speech. Silence, enacted on the stage, also resists the Machiavellian twofacedness of Edmund, that master rhetorician. When Lear in the latter part of the play is reduced to strings of repetitions (‘Howl, howl, howl, howl!’ as he discovers Cordelia’s dead body; or ‘Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill’; or closer to the theme of ‘nothing’ ‘Never, never, never, never, never’), we experience another version of the rhetoric of silence, the acknowledgement of the unutterable, the literally unspeakable. Like the syntactical breakdown of Othello’s language in the scene of his swooning fit, Lear’s repeated iterations of the same word over and over again, without subject tor object, and without any rhetorical gesture of control, mark the very limit of language as communication.

At this point in the play, however, Cordelia’s silence is an antidote to the unfeeling hypocrisy of Goneril and Regan, the ‘glib and oily art’ of their glozing speech. Silence, enacted on the stage, also resists the Machiavellian twofacedness of Edmund, that master rhetorician. When Lear in the latter part of the play is reduced to strings of repetitions (‘Howl, howl, howl, howl!’ as he discovers Cordelia’s dead body; or ‘Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill’; or closer to the theme of ‘nothing’ ‘Never, never, never, never, never’), we experience another version of the rhetoric of silence, the acknowledgement of the unutterable, the literally unspeakable. Like the syntactical breakdown of Othello’s language in the scene of his swooning fit, Lear’s repeated iterations of the same word over and over again, without subject tor object, and without any rhetorical gesture of control, mark the very limit of language as communication.

From the first scene on, other characters will seek to evade the prevailing duplicity of language in yet another way, by disguising their voices. Thus Kent becomes the country man “Caius,’ whose plainness of speech is so irritating to the Duke of Cornwall, and who puts on a mockingly courtly language to try to expose the follies of flattery and verbal ‘accommodation’ (‘Sir, in good faith, in sincere verity,/Under th’allowance of your great aspect,’ and so on). The servile language he mocks resembles that of Osric, the foppish courtier in Hamlet, whose words were so fashionably contorted they required translation. In a similar way Edgar, eschewing the ornate duplicities of the court, becomes not only ‘Poor Tom,’ the ‘Bedlam beggar’ with his nonsensical jingles and visions of fiends, but also the rustic with the strange dialect who pretends to rescue the blind Gloucester at the bottom of Dover ‘cliff.’ Gloucester almost recognizes his disguised son by his voice – ‘Methinks thy voice is altered;’ ‘Methinks you’re better spoken’ – and is hastily corrected by Edgar: ‘You’re much deceived. In nothing am I changed/But in my garments.’ Since Gloucester is blind, he cannot see that Edgar’s garments, alone, remain unchanged throughout the scene.

The dark side of the rhetoric of silence, the language of limitation and the limitation of language, is that great yawning chasm of ‘nothing’ that pervades the play, emanating from the remarkable and encyclopedic first scene. ‘Nothing will come of nothing’ is Lear’s threat, based on his interpretation of Cordelia’s silence. And ‘Nothing will come of nothing’ will become Lear’s own living epitaph in the acts and scenes to come. ‘Nothing’ – the opposite of ‘everything,’ of ‘accommodation.’

‘They told me I was everything; ‘tis a lie, I am not ague-proof,’ says Lear near the close of his tragedy. (4.5.102). Both Lear and Gloucester will make the mistake of taking themselves for everything. Both are tortured by that haunting word ‘nothing’ until they become nothing. Later in the first act Lear’s Fool will ask his master, ‘Can you make no use of nothing, nuncle?’ and will be told, Why no, boy, Nothing can be made of nothing.’ But nothing is what Lear has left himself, in divesting himself of kingdom and power. As the Fool points out, referring to the new Arabic numbers that were replacing Roman numerals, the innovation of the nought, the figure zero, from the Arabic word ‘cipher,’ meaning ‘empty,’ ‘Now thou art an O without a figure. I am better than thou art, now. I am a fool; thou art nothing.’

When he pretends to protect his father by theatrically ‘concealing’ a piece of paper, the bastard Edmund claims that he is reading ‘nothing,’ which is true, since what he has in his hand is a false letter he himself has fabricated to implicate his legitimate brother, Edgar. But Gloucester, like Lear, will fall into the trap. ‘The quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself,’ he objects. The paper must be something. And so Gloucester make something of it, getting from Edmund the ‘auricular assurance’ that so closely resembles Iago’s equally deceiving ‘ocular proof’ in Othello – evidence, in fact, of nothing at all. Gloucester ironically praises his son’s behavior as that of a ‘[l]oyal and natural boy’ (2.1.83). Gloucester means ‘according to nature,’ but a ‘natural’ son (from the Latin filius naturalis and Middle French fils naturel) was an illegitimate child, born outside of marriage. Shortly we will see the legitimate son, Edgar, stripped of his rightful place and forced for safety’s sake to change his identity into that of the beggar ‘Poor Tom,’ declare, ‘Edgar I nothing am’ (2.2.178). We could read this as ‘I am not Edgar’ but also ‘As Edgar, I am nothing.’ The play moves remorselessly from its first scene of ‘everything’ (accommodation, luxury, comfort, and security) toward a clear-eyed and scarifying contemplation of ‘nothing.’ And the immediate cause is Lear’s own lack of self-knowledge.

When he pretends to protect his father by theatrically ‘concealing’ a piece of paper, the bastard Edmund claims that he is reading ‘nothing,’ which is true, since what he has in his hand is a false letter he himself has fabricated to implicate his legitimate brother, Edgar. But Gloucester, like Lear, will fall into the trap. ‘The quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself,’ he objects. The paper must be something. And so Gloucester make something of it, getting from Edmund the ‘auricular assurance’ that so closely resembles Iago’s equally deceiving ‘ocular proof’ in Othello – evidence, in fact, of nothing at all. Gloucester ironically praises his son’s behavior as that of a ‘[l]oyal and natural boy’ (2.1.83). Gloucester means ‘according to nature,’ but a ‘natural’ son (from the Latin filius naturalis and Middle French fils naturel) was an illegitimate child, born outside of marriage. Shortly we will see the legitimate son, Edgar, stripped of his rightful place and forced for safety’s sake to change his identity into that of the beggar ‘Poor Tom,’ declare, ‘Edgar I nothing am’ (2.2.178). We could read this as ‘I am not Edgar’ but also ‘As Edgar, I am nothing.’ The play moves remorselessly from its first scene of ‘everything’ (accommodation, luxury, comfort, and security) toward a clear-eyed and scarifying contemplation of ‘nothing.’ And the immediate cause is Lear’s own lack of self-knowledge.

At the close of the opening scene the audience hears Goneril and Regan, who have flattered their father grossly throughout the public ceremony of the love test, now speak of him privately as a senile fool. ‘You see how full of changes his age is,’ says Goneril, and Regan is quick to agree: ‘Tis the infirmity of his age; yet he hath ever but slenderly known himself.’ She is not entirely wrong, if Lear can commit the action with which he opens the play, the irreversible action that calls down his tragedy upon him. ‘Only we shall retain/The name and all th’addition to a king.’ To retain ‘only the name,’ the title without the power, is of course impossible. Kent, the loyal friend and vassal, is to Lear in this play what Horatio is to Hamlet, what Banquo is to Macbeth – an index of normality, a foil for the excesses of the tragic hero. Kent calls the abdication folly, and the rejection of Cordelia madness, and he addresses, directly and firmly, the question of retaining ‘only the name’:

Royal Lear,

Whom I have ever honoured as my king,

Loved as my father, as my master followed,

As my great patron thought on in my prayers –

‘Royal Lear,’ ‘king,’ ‘father,’ ‘master,’ ‘patron’ – these are the necessary social roles and costumes of accommodated man, and Lear rejects them all, earning Kent’s blunt anger. ‘Be Kent unmannerly/When Lear is mad. What wouldst thou do, old man?’ and, ‘To plainness honour’s bound/When majesty falls to folly.’ Thus once again in this great opening scene we hear a note that will be sounded repeatedly. Lear is already mad here, although not yet in the sense of the frantic disorientation that will overtake him by the third act. He is metaphorically, though not yet literally, mad. And he is no longer King, patron, royal Lear. Instead he has become simply – and impotently – an ‘old man.’ The same pointed reduction will take place again at the end of act 2, when Gloucester refers to Lear with customary respect as ‘the King’ – ‘The King is in high rage’ (2.2.459) – and Cornwell and Regan dismiss him merely as the ‘old man.’ For in stripping himself of these necessary roles, and the powerful trappings of kingship, Lear also strips himself of dignity, fear, respect – and friends. ‘Out of my sight!’ he rails at Kent, and Kent, again prophetically, answers, ‘See better, Lear’ (1.1.155-56). Lear’s moral blindness is as absolute in this opening scene as Gloucester’s physical blindness will be later in the play, and Lear divests himself not only of his kingdom, his daughter Cordelia, and his roles as King and father, but also of those other crucial roles as master and patron, for he divests himself of Kent. The faithful Earl of Kent is banished, his banishment ordained to take place on the sixth day, with a resonance of the banishment of Adam from Eden. He departs with: ‘Thus Kent, O princes, bids you all adieu; /He’ll shape his old course in a country new.’ Like Celia in As You Like It going forth into the Forest of Arden (‘Thus go we in content/To liberty and not to banishment’), or Coriolanus defiantly rejecting Rome (‘I banish you’ [emphasis added]), Kent claims the comparative liberty of exile, when oppression and injustice inhabit the court; ‘Freedom lives hence, and banishment is here.’ With the division of the kingdom and the rejection of Cordelia and Kent, Lear’s Britain undergoes a fall. (Kent returns immediately in the disguise of a common man, doffing his exalted rank. ‘How now, what art thou?’ the King will demand of him, and he will respond simply, ‘A man, sir.’

All appearance of order and rank has disappeared. The great emblematic procession that trailed across the stage – king, nobles, daughters, dependents – is broken up, disrupted. Such a procession, a visual icon of royal power, would have been clearly recognizable to Shakespeare’s audience as the sign of contemporary – early modern – sequence and succession, however situated the events of the play might be in the history of early Britain. The sumptuous trappings of civilization are revealed as fictive coverings, and the play’s innate primitivism, which goes even further back than Norman or Celtic Britain, begins to reveal itself. This is not, after all, a civilized world. It is a world of monster, cannibals, and heraldic conflict. ‘Come not between the dragon and his wrath,’ Lear commanded Kent as Kent tried to intervene on behalf of Cordelia (1.1.120). Lear is both the dragon, the sign of Britain from Norman times onward, and the wrathful king – a king who thinks he has the power of an angry god. No sooner does he say this than the play is flooded with images of unnatural monsters, monsters that feed upon themselves and their young:

The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite…

(1.1.114-116)

Ingratitude, thou marble-hearted fiend,

More hideous when thou show’st thee in a child

Than the sea-monster –

(1.4.220-222)

How sharper than a serpent’s tooth is it

To have a thankless child…

(1.4.251-252)

Humanity must perforce prey on itself,

Like monsters of the deep.

(Quarto, 16.48-49)

Lear and others now begin to speak of pelican daughters; of tigers, not daughters; of dog-hearted daughters; of sharp-toothed unkindness, like a vulture; of nails that flay a wolfish visage. A whole cluster of monsters is summoned up, in effect, by Lear’s initial action in dividing his kingdom, and in wishing to do what no human being and certainly no king can do: to unburdened crawl toward death.

This marvelous, panoramic opening scene, then, poses almost all the issues and introduces almost all the images that will serve to focus the play. yet the Lear plot is only one of the two major plots that intertwine in King Lear. What we have been calling the ‘opening scene’ is framed by two episodes that involve the key figures of Gloucester and his bastard son Edmund. The play is designed with a very clear symmetry: two old men, each with a loyal child he mistakenly considers disloyal (Cordelia and Edgar), and disloyal children or a child he at first thinks loyal and natural (Goneril, Regan, and Edmund). In fact, one Restoration editor, Nahum Tate, dissatisfied with the tragic ending of the play, rewrote it to conclude with a marriage between Cordelia and Edgar. And lest we think this a curious aberration of those times, we should note that the Tate version of the play, ‘reviv’d with alterations,’ to quote his title page, held the stage from 1681 to 1838, as the ‘improv’d version of King Lear, correcting the barbarisms of Jacobean times.

The symmetries provided by these two plots, the Lear plot and the Gloucester plot, are not merely dynastic or structural. Lear, whose error is a mental error, the error of misjudgment in dismembering his kingdom, is punished by a mental affliction, madness. Gloucester, whose sin is a physical sin, lechery, is punished in the play by a physical affliction, blindness. As Edgar says bitterly to Edmund, ‘The dark and vicious place where thee he got/Cost him his eyes’ (5.3.162-163). The blinding of Gloucester is also, of course, a literal evocation of this imagined justness of punishment, an eye for an eye. The manifold mythic and literary associations of blindness, from Oedipus to Freud, link that condition with sexual knowledge, with castration, and with ‘insight.’ (As Gloucester will observe ruefully, underscoring the paradox, ‘I stumbled when I saw.’)

The play presents two different paradigms of biblical suffering, juxtaposed and paralleled. Lear is a Job-like character, a man who has everything (family, wealth, honor) and loses everything. The mock trial in scene 13 (in the Quarto only) restages the story of Job and his comforters, here played by the tragically inadequate figures of the Fool and ‘Poor Tom.’ We hear Lear, like Job, quest perpetually for patience: ‘You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need” (2.2.437); ‘I will be the pattern of all patience.’I will say nothing.’ (3.2.36-37); ‘I can be patient, I can stay with Regan,/I and my hundred knights’ (2.2.395-393); ‘I’ll not endure it’ (1.3.5) – and then, two acts later, ‘Pour on, I will endure’ (3.4.18). But if Lear is a Job, quick to anger and quick to rail against heaven, Gloucester is a more passive and accepting Christian sufferer, a man who is willing to believe that ripeness is all, that men must endure their going hence, even as their coming hither. As if to emphasize the degree of his abnegation, Gloucester begins to speak of the ‘kind gods’ from the moment his eyes are put out.

The latter part of King Lear places an increasingly heavy emphasis on this emblematic Christian theme in language and in staging. Cordelia is arguably the real ‘Christ figure’ in the play, speaking of her ‘father’s business’ and making her final appearance in a gender-reversed Pieta, held in the arms of a grieving Lear. Some productions of the play have also emphasized Edgar’s evident Christ-like qualities; in Peter Brook’s film (1971) Edgar is stabbed in the side with a spear as he cries out at the spectacle of death (‘O thou side-piercing sight!’). Yet as with all Shakespearean evocations of allegory, whether religious, mythological, or political, the Christian undertones and overtones in Lear work best when they are allowed to augment the dramatic action rather than displace it. The power of King Lear and its place in our cultural imaginary depend above all, at least for a modern audience, upon its depiction of a human story of love, suffering, and loss.

The gods mentioned in this play are as various as the mythological strains that underpin it. The first mentions are of pagan gods; Lear swears by Apollo and appeals to ‘the thunder-bearer’ and to ‘high-judging Jove’ (2.2.392, 393). In 1606 Parliament passed ‘An Act to Restrain Abuses of Players’; it stipulated that ‘no person or persons…in any stage play, interlude, show, maygame, or pageant’ might ‘jestingly or profanely speak or use the holy name of god or of Christ Jesus, or of the Holy ghost or of the Trinity.’ Thus, swearing by the name of the Christian God was forbidden by law. Nonetheless the play moves inexorably toward the contemplation of a Christian solution. The pagan gods become at various times kind gods, clearest gods, just gods – or, in one of the play’s most famously despairing lines, gods as ‘wanton boys.’

In fact, what we have in King Lear are not only two modes of suffering and two kinds of godhead but also two conceptions of tragedy that are cited explicitly and made to play against each other. Familiar from earlier Shakespearean history plays, and notably from Richard III, these two modes can be described, in shorthand terms, as cyclical and linear, or as ‘medieval’ and ‘early modern.’ As we have often noticed, one popular pattern for tragedy, as exemplified in the kinds of medieval literary works called ‘falls of princes,’ was that of the wheel of Fortune. Life was imagined – and often depicted in woodcuts and engravings – as a great wheel. Each man’s and each woman’s life reached a point of greatest height, greatest prosperity, from which he or she would, ultimately, fall.

We hear a great deal about this kind of tragedy in King Lear. The disguised Edgar speaks of what it is like to be ‘at the worst,’ at the bottom of Fortune’s wheel, only to find that, since he can say he is at the bottom, he is not yet really there. (He is in fact immediately confronted with the spectacle of his blinded father, and is moved to observe, ‘I am worse than e’er I was’ (4.1.26). This is another clear example in the play of the rhetoric of silence, the unutterability of extremes in emotion.) Likewise the disguised Kent, finding himself ignobly place in the stocks – a punishment that angers his master, Lear, because it is an insult, a disregard of rank – resigns himself to the necessity of patience: ‘Fortune, good night;/Smile once more; turn thy wheel’ (2.2.157-158). Lear’s Fool, too, believes in this kind of cycle. He sees that his own prospects are dependent upon the vagaries and vicissitudes of Fortune: ‘Let go thy hold when a great wheel runs down a hill, lest it break thy neck with following; but the great one that goes upward, let him draw thee after’ (2.2.238-240). And as he lies dying at the end of the play even the bastard Edmund, who had cynically observed, ‘The younger rises when the old doth fall’ (3.3.22), accepts with fatality his reversal of fortune: ‘The wheel is come full circle. I am here.’ (5.3.164).

This notion of Fortune’s wheel is omnipresent in the play, but it is consistently in tension with another pattern, one often associated with Christianity, but also with tragedy in its classical form: the idea of the fortunate fall. ‘The gods throw incense on our sacrifices;’ individual human suffering and human loss are only aspects of the quest for a larger knowledge of the nature of humanity and mortality. Thus the idea of exemplary sacrifice – Christ died for the sins of mankind – is sutured to the dramatic action, at the same time that it is naturalized and humanized. Both Lear and Gloucester ‘die’ in the play – indeed each dies not once but twice, and each is ‘reborn.’ Gloucester believes that he has leapt from Dover ‘cliff’ and has been miraculously preserved to life; Lear in the fourth act dies out of his madness and into fresh garments, out of the grave and into the world again. When they die a second time – when they die ‘for real,’ so to speak – is the second (literal) ‘death’ likely to be any more final than the first (symbolic) one? The play itself is ‘reborn’ (today we often say ‘revived’) each time it is performed. One of the functions of Jacobean tragedy is to take this exemplary and educative form: to present us with great figures who die for our sins and make mistakes that could be ours, and whose tragedies take place so that ours will not, or need not. Literary tragedy is in this formal sense a scapegoat, substitute, or safety valve. Its cultural value is not only aesthetic but also ameliorative and apotropaic, warding off danger.

But the tragedy of King Lear begins at the other end of the scale, not with the supernatural but with the natural. As we have seen, Cordelia’s claim of a natural ‘bond’ between parent and child is juxtaposed to an image of the ‘natural’ in its most anarchic and destructive form, in the person of Edmund, the natural, or bastard, son of the Duke of Gloucester. Edmund’s villainy is not equated with his bastardy, although the range of meanings of ‘natural’ offers an effective amplification of the serious rumination on the nature of ‘nature’ throughout the play. Philip Falconbridge, the ‘Bastard’ in King John, is that play’s martial and patriotic center, far more heroic than his conservative (and ‘legitimate’) brother, Robert. The great speech on ‘bastardy’ and baseness should rather be compared to Richard of Gloucester’s comparably energetic speech on ‘deformity’ at the beginning of Richard III. In both cases the Machiavellian speaker seduces the audience, using his supposed deficiency as both a rhetorical excuse for aberrancy and a gauntlet thrown down daringly to challenge the status quo. Edmund is a close relation of Iago [MY NOTE: Much more on Edmund from Harold Bloom in later posts] and of Richard III in his contempt for what he regards as passive sentimentalism. Like them he is a Machiavel and Vice figure, a character who draws strength from his own contrariness. Not for him the old-fashioned view that ‘our stars’ govern our behavior: ‘I should have been what I am had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing’ (1.2.119-121). He revels in disorder, takes pleasure in anarchy. In the early part of the play, when all around him other characters either begin to doubt their own identities or feel it prudent to conceal them, Edmund alone is never doubtful. His masterful manifesto is addressed to Nature, the goddess he elects as the patroness of natural children, the children of disorder:

Thou, nature, art my goddess. To thy law

Thou, nature, art my goddess. To thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why ‘bastard?’ Wherefore ‘base,’

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With ‘base,’ with ‘baseness, bastardy – base, base’ –

Who in the lusty stealth of nature take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth within a dull, stale, tired bed

Go to th’ creating a whole tribe of fops

Got ‘tween a sleep and wake? Well then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land.

Our father’s love is to the bastard Edmund

As to th’ legitimate. Fine word, ‘legitimate.’

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall to th’ legitimate. I grow, I prosper.

Now gods, stand up for bastards!

The language of energetic and entrepreneurial ‘prosperity’ (‘I grow, I proper’) seems to counter, and to replace, the repressive economics of Lear’s love test (‘deeds,’ ‘worth, ‘etc.). It is almost as if Lear’s rejection of the ‘true’ daughter, Cordelia, has brought forth this outburst, so that prosperity now resides not among the orderly processes of rule and kingship but instead in a celebration of the anarchy of sex and law. The next invocation to Nature we hear will be Lear’s curse called down upon Goneril: ‘Into her womb convey sterility.’ (1.4.240).

Nature goes from pure fecundity to agent of barrenness, and we might notice here how very quickly it is that Lear, too, falls. Even within that emblematic first scene his fall from love to wrath is astonishingly swift, and the conference of the disaffected daughters afterward confirms the audience’s misgivings. By the end of the first act the King is nothing but an ‘Idle old man,/That still would manage those authorities/that he hath given away!’ (Quarto, 3.16-18) – at least in Goneril’s view. Lear is now for the first time joined onstage by his Fool. It is no accident that the fool appears just at the moment when Lear has begun to act like a fool. We will see shortly the degree to which this sublime Fool acts as a mirror for the King. Lear’s self-stripping, of lands, of friends, of his treasured daughter, is now converted into a stripping by his elder daughters,, so that he is, for the first time in the play, (and, again, quite early), reduced to a tragic quest for self – all the more tragic because it is performed as a piece of unbecoming foolery, a piece of mumming, what Goneril calls one of his ‘new pranks”:

Does any here know me? This is not Lear.

Does Lear walk thus, speak thus? Where are his eyes?

……………………………………

[Ha], waking? ‘Tis not so.

Who is it that can tell me who I am?

‘Lear’s shadow,’ replied the Fool. Eyes, speaking, and waking are all familiar and indicative themes, and from this point the play will proliferate not only images of this kind but also insistent questions of identity. Goneril, the resistant audience to this poignant scene, is determined to strip her father of half his attendant knights, and it is this issue that calls down upon her his curse, delivered at the end of Act I. Again, this must seem early to us, in view of the pattern of the usual tragic fall. Here is Lear:

Hear, nature; hear, dear goddess, hear:

Suspend thy purpose if thou didst intend

To make this creature fruitful.

Into her womb convey sterility.

Dry up in her the organ of increase,

And from her derogate body never spring

A babe to honour her…

Lear wishes upon his eldest daughter a fate that will leave her not only without a child but also without an heir. Since she has inherited part of his kingdom, this is a wish that, if granted, would bring to an end the rule he has granted her. One of the many connotations of the word ‘nothing’ in this period was a slang reference to the female sexual organs (compare Hamlet’s lines on the ‘no thing’ that lies ‘between maids’ legs). Thus Lear’s intemperate words to Cordelia (‘Nothing will come of nothing’) are now transposed into his physical curse upon Goneril – that nothing (no child) should come of her ‘no thing.’)

——————————–

——————————-

And that’s what Marjorie Garber had to say about Act One – thoughts?

My next post: Thursday evening/Friday morning – more on Act One.

you are actually a just right webmaster. The website loading velocity is incredible.

It sort of feels that you’re doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork. you’ve done

a wonderful task in this topic!

Great post!

I think Garber’s absolutely right that the first scene has the quality of ‘a well-rehearsed fairy-tale’, and she beat me to the punch (drat!) in comparing Cordelia to Hamlet – in both cases, their contributions are like a record skipping in the midst of all this ceremony. I certainly don’t agree with Bloom that Lear represents patriarchal sublimity. The forces which begin to annihilate him are anything but moral, but I don’t think that, within the play’s cosmos, Lear could be anything but hopelessly inadequate as a monarch. Nothing in the first scene is sincere, except for Cordelia, Kent, France and Lear’s already impotent rage.

There’s one line that always puzzles me: Lear giving up his power ‘while we / Unburdened crawl toward death.’ The word ‘unburdened’ obviously expresses more than Lear knows, pointing forward in the play towards ‘unaccomodated man’ but crucially it also makes sense within the local context of the scene and Lear’s character at this stage. But it seems very weird to me that he is also talking about crawling toward death at this point. There’s a total lack of dignity or grandeur in the statement, which seems at odds with the folly of Lear divesting his burdens but retaining the name and additions of a king – or the pomp and the glory. Is Shakespeare junking character here in favour of broader irony? Or is Lear making a joke which is reliant upon his words being so clearly inappropriate (he thinks) for such a self-evidently majestical creature? I don’t know. If I were an actor, I wouldn’t be quite sure of how to play that line.

Jackson: In my post for this evening, I mention the extensive use of “un” throughout this play. And as for crawling towards death…I think of it in terms of Jaques’ Seven Ages of Man — reverting back to the way one was when was “unburdened” by life, a second childhood perhaps.

That’s a really good point! I guess it seemed so macabre to me that I didn’t pick up on that. Poor Lear, though – he only gets to be actually childlike in his tantrums.

I liked how Ian McKellen delivered the line. King Lear is 80 years old. He’s thinking about the end of life.

This is the play I have seen the most and not read until now. It is wonderful to read, as Bloom suggests.

It strikes me that the character groupings in King Lear center around five (is that pentameter?) in all its variations of structure. Might Shakespeare’s character groupings and regroupings parallel the rhythm of his genius for wordplay? The characters become “the syllables” which create a rhythmic structure. Like dance or music but with the characters themselves not only in their words but in their groupings and regroupings–in their juxtapositions -which holds this play together even as the kingdom is divided and all hell breaks loose. There’s this poetic structure underneath that is holding it together. I’m a little out of my league here, but I keep seeing this rhythm around the number five–sometimes three and two OR two and two and one OR one and one and three. There is a rhythm woven into this plays structure that seems to supply endless permutations.

I keep coming back to one of Gloucester’s opening observations “…for equalities are so weighed that curiosity in neither can make choice of either’s moiety.”

A good line to keep coming back to. 🙂