Titus Andronicus

Act Four

By Dennis Abrams

———————-

Act Four: Lavinia identifies her attackers (and lets Marcus know she was raped) by pointing to the tale of Philomel in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and by inscribing their names in the sand. Titus responds to the news by sending a gift of weapons with a message to Chiron and Demetrius, know that they will be unable to decipher it. Aaron, however does, and realizes that Titus means to take his revenge, but he is distracted by the arrival of a nurse with his newborn baby by Tamora, which she wants killed because his dark skin will let the secret of her relationship with Aaron out. Aaron saves his son’s life by killing the nurse instead to keep her from talking. Titus, meanwhile, has apparently gone mad: he mourns the absence of Justice, and orders arrows to be shot into the sky bearing messages for the gods. At the palace, Saturninus find the arrows that Titus had shot, and also is alarmed to learn that Lucius is marching on Rome at the head of a Goth army.

—————————

A question: Am I misreading this, or did it seem that no one seemed particularly interested in getting revenge for Lavinia until it was learned that she had also been raped?

And another question: Wouldn’t we be calling it post modern or some such thing today if a character in a book or play makes reference (or even drags out the text) that they are based on? And can’t you see the scene of Lavinia, chasing after poor Lucius’s son who happens to be carrying a copy of Ovid, flapping her stumps and scaring the hell out of him, being done as pure slapstick albeit horrific comedy?

—————–

I’d like to backtrack a bit, to Frank Kermode’s take on what seems to me to be one of the most important and fascinating speeches in the play so far: Marcus’s reaction upon seeing Lavinia’s maimed and bleeding body:

Who is this? My niece, that flies away so fast?

Cousin, a word; where is your husband?

If I do dream, would all my wealth would wake me!

If I do wake, some planet strike me down,

That I may slumber an eternal sleep!

Speak, gentle niece: what stern ungentle hands

Hath lopp’d and hew’d, and made thy body bare

Of her two branches, those sweet ornaments

Whose circling shadows kings have sought to sleep in,

And might not gain so great a happiness

As half thy love? Why dost not speak to me?

Alas, a crimson river of warm blood,

Like to a bubbling fountain stirr’d with wind,

Doth rise and fall between thy rosed lips,

Coming and going with thy honey breath.

But sure some Tereus hath deflow’red thee,

And lest thou shoulder detect him, cut thy tongue.

Ah, now thou turn’st away thy face for shame!

And notwithstanding all this loss of blood,

As from a conduit with three issuing spouts,

Yet do thy cheeks look red as Titan’s face

Blushing to be encount’red with a cloud.

Shall I speak for thee? shall I say ‘tis so?

O that I knew they heart, and knew the beast

That I might rail at him to ease my mind!

Sorrow concealed, like an oxen stopp’d,

Doth burn the heart to cinders where it is.

Pair Philomela, why, but she lost her tongue,

And in a tedious sampler sew’d her mind;

But lovely niece, that mean is cut from thee.

A craftier Tereus, cousin, has thou met,

And he hath cut those pretty fingers off

That could have better sew’d than Philomel.

Tremble like aspen leaves upon a lute,

And made the silken strings delight to kiss them,

He would not then have touch’d them for his life!

Or had he heard the heavenly harmony

Which that sweet tongue hath made,

He would have dropp’d his knife, and fell asleep,

As Cerberus at the Thracian poet’s feet.

Come let us go, and make they father blind,

For such a sight will blind a father’s eye.

One hour’s storm will drown the fragrant meads,

What will whole months of tears thy father’s eyes?

Do not draw back, for we will mourn with thee.

O, could our mourning ease thy misery!

“The first audience would have had a very good idea of what Marcus is up to here. He is making poetry about the extraordinary appearance of Lavinia, and making exactly as he would if he were in a non-dramatic poem. To a modern director the scene is something of an embarrassment: Marcus, instead of doing something about Lavinia, who, as his account of the matter confirms, is in real danger of bleeding to death, makes a speech lasting a good three minutes. Confronted with an obvious need to act, at first he wishes he could be planet struck into sleep. There is a neat play on the antithesis gentle-ungentle. Marcus compared Lavinia to a lopped tree, and the blood pouring from her mouth to a crimson river. Since it pours also from her hands, she is likened to a garden ornament, a conduit with three spouts. Her breath, despite all the blood, is still described as ‘honey,’ as if this were an immutable Homeric epithet. Her cheeks are compared to the setting sun.

Marcus, a well-educated Roman in the hands of a well-educated English poet, aptly adduces a Senecan tag or proverb about unspoken grief stopping the heart. He is quick to see as apposite the story of the rape of Philomel by Tereus, which happens to be the myth on which the play is based on (as the text often reminds us). But Tereus only tore out Philomel’s tongue, leaving her the option of revealing her assailant’s identity in a piece of sewing. The new rapist has taken notice of this and outdone him by cutting off his victim’s h ands as well. Marcus remembers Lavinia’s voice and the sight of her hands playing on a lute, not omitting a reference to the music with which Orpheus charmed Cerberus in the underworld. We are not to think it absurd that he expresses a wish he could ease his mind by giving the culprit a good scolding. He leaves us in no doubt that he commands the means to explain why he finds the whole scene very upsetting, and even thinks of blinding Lavinia’s father to spare him the same sight.

We should find this verse ridiculous, but insofar as it belongs in a theatre, that theatre is very different from the theatre of Hamlet or Macbeth or Coriolanus, and the task of the poet very differently conceived. We must not look here for plausible action, not even for plausible inaction or silent horror. In Peter Brook’s memorable production of 1955, the speech was entirely cut; Marcus wasn’t even on stage when Lavinia (Vivien Leigh) entered with red ribbons streaming from her wrists and mouth. [MY NOTE: See the still in my last post.] That was a way of preserving the horror without the language that in the time of the early Shakespeare seemed a good way of representing it, a poet’s way, but now embarrassing. Trevor Nunn, in 1972, cut twenty-nine lines from Marcus’s speech, leaving us with neither one thing nor the other, but one really needs to choose, all or nothing; Deborah Warner, in her 1988 version, restored the whole speech.

The latest Arden editor, from whom I borrow the stage history above, is a keen advocate of the merits of Titus Andronicus, and he defends Marcus’s speech by claiming to find it in it an acceptable modern psychology. Marcus has to learn to confront suffering. ‘The working through of bad dream into clear sight is formalized in Marcus’ elaborate verbal patterns; only after writing out the process in this way could Shakespeare repeat and vary it in the simple, direct, unbearable language at the end of Lear: “Look there, look there!’… And a lyrical speech is needed because it is only when an appropriately inappropriate language has been found that the sheer contrast between its beauty and Lavinia’s degradation begins to express what he has undergone and lost.’ But this interpretation is surely as misguided as it is honourable. It may be true that the kind of thing we find in Titus was a preparation, something a poet at thirty might think right, given the sort of piece he was writing – a drama affected by the example of Seneca and, even more so by the example of Ovid, who was the source of the Philomel/Lavinia plot, as of much else in Shakespeare. Titus is probably his most learned play, and poets needed to be learned. But playwrights needed another kind of erudition than that appropriate to non-dramatic poetry. There was obviously an overlap of skills, but theirs was a different craft. It soon became apparent that the trade of the dramatic poet was different and increasingly remote from the conventional, bookish rhetorical display. Not that rhetoric was abjured, merely that it was powerfully adapted to a different task and greatly changed in the process. Of course prentice work in a more formal rhetoric could be thought as a useful, perhaps at the time an essential, preparation.”

—————–

And yet…

Couldn’t one also say that while Marcus’s first reaction is not to deal with Lavinia’s injuries (first-aid anyone?), but to reach for a classical precedent, that of Philomel’s rape in Book 6 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses? And in addition, that the way in which Marcus anesthetizes or blunts his own anguish by comparing her bleeding mouth to a “bubbling fountain” and her chopped off limbs to “sweet ornaments” is almost and deliberately confrontational. Marcus’s speech serves the purpose, I think of forcing us to gaze with horror at the spectacle of Lavinia, and forces to contemplate the very real and terrible gulf between his florid words and theatrical reality; made even more striking, I think, by the contrast between his words and the otherwise fairly straightforward and direct language found in the rest of the play.

———————————–

I wanted to include this, from Maurice Charney, on Aaron the Moor:

“The most brilliant and fully developed character in Titus Andronicus is the Moor Aaron, a free-floating mercenary like the Moor Othello, who is brought captive to Rome in Titus’s triumph. Aaron is also the lover of Tamora, Queen of the Goths, and in his first speech in the play, a vaunting soliloquy imitating Marlowe’s ‘mighty line,’ Aaron boats that he holds Tamora prisoner,

fettered in amorous chains,

And faster bound to Aaron’s charming eyes

Than is Prometheus tied to Caucaus.

The classical allusion is altogether typical of the heightened style of the play. Aaron is a grand adventurer like Tamburlaine, the Scythian shepherd, who expects to make his fortune now that Tamora is Empress of Rome.

Away with slavish weeds and servile thoughts!

I will be bright and shine in pearl and gold

To wait upon this new made empress.

The style is buoyant, and it includes a specifically sexual component that is foreign to Marlowe.

Aaron will ‘mount’ Tamora’s ‘pitch’ – a term from falconry, but with a double entendre here encouraged by the word mount. Later Aaron encourages Demetrius and Chiron in their plan to rape Lavinia: ‘Why then, it seems, some certain snatch or so/Would serve your turns.’ Later, when we hear about Tamora’s black baby, Aaron shocks even the sons of Tamora. ‘I have done thy mother.’ This sounds like the sexual boasting associated with the game of the dozens.

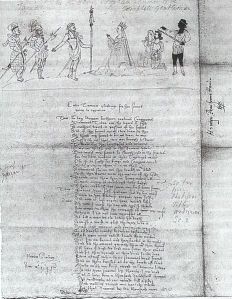

An extraordinary drawing from 1595, attributed to Henry Peacham, of a composite scene from Titus Andronicus may represent the way the characters looked on stage. Titus is dressed in a Roman toga, and other characters are attired in a mixture of Roman and Elizabethan military costumes, but Aaron is the most striking figure of all. He is coal-black, Negroid, with thick lips, and wears an imitation of light Roman body armor. The black Aaron looks forward, ironically, to the white Iago. Both are wonderfully improvisatory, cheerful, frank, and eager to remain on good terms with the audience. In this sense Aaron is the prototype for all Shakespeare’s later villains. He establishes the need for the villain to be sardonic. When he tricks Titus into letting him cut off his hand, Aaron remembers that when he had it, he drew himself apart ‘And almost broke my heart with extreme laughter.’ (5.1.113). And in the upshot, ‘When for his hand he had his two sons’ heads’, Aaron the onlooker ‘pried me through the crevice of a wall…/Beheld his tears and laughed so heartily/That both mine eyes were rainly like to his.’ This merry device resembles the mischievous and deadly pranks of Barabas and Ishamore in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta. Aaron is unrepentant and diabolic, and in his rabid atheism he scorns the Christian god of the Andronici. It comes as a surprise, then, that Aaron is so devoted to his black baby, who is a kind of heroic Caliban in miniature. In later plays the villain is not endowed with such an endearing, redeeming trait.

An extraordinary drawing from 1595, attributed to Henry Peacham, of a composite scene from Titus Andronicus may represent the way the characters looked on stage. Titus is dressed in a Roman toga, and other characters are attired in a mixture of Roman and Elizabethan military costumes, but Aaron is the most striking figure of all. He is coal-black, Negroid, with thick lips, and wears an imitation of light Roman body armor. The black Aaron looks forward, ironically, to the white Iago. Both are wonderfully improvisatory, cheerful, frank, and eager to remain on good terms with the audience. In this sense Aaron is the prototype for all Shakespeare’s later villains. He establishes the need for the villain to be sardonic. When he tricks Titus into letting him cut off his hand, Aaron remembers that when he had it, he drew himself apart ‘And almost broke my heart with extreme laughter.’ (5.1.113). And in the upshot, ‘When for his hand he had his two sons’ heads’, Aaron the onlooker ‘pried me through the crevice of a wall…/Beheld his tears and laughed so heartily/That both mine eyes were rainly like to his.’ This merry device resembles the mischievous and deadly pranks of Barabas and Ishamore in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta. Aaron is unrepentant and diabolic, and in his rabid atheism he scorns the Christian god of the Andronici. It comes as a surprise, then, that Aaron is so devoted to his black baby, who is a kind of heroic Caliban in miniature. In later plays the villain is not endowed with such an endearing, redeeming trait.

The savagery and violence of Titus Andronicus are connected with the historical period in which the play is imagined to take place: in the late Roman Empire around the fourth or fifth century A.D., when Rome was seriously threatened by barbarian hordes. In the first scene, Marcus has to remind his brother, ‘Thou art a Roman, be not barbarous,’ and there is a definite feeling of barbarity in the ritual slaughter of Alarbus, a prisoner of war and the eldest son of Tamora, Titus’s impetuous killing of his own son Mutius, and the carrying off of Lavinia when she is betrothed to Saturninus. ‘Suum cuique’ says Marcus, which is later echoed by Bassianus. ‘Rape, call you it, my lord, to seize my own?’ This is not the high moral Rome of Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, or even Coriolanus, all of which are based on Plutarch’s Lives. It is more the Rome of Tarquin in The Rape of Lucrece. Both the play and the poem have an archaic, primitive quality that Shakespeare never repeated. Rape in both works is a political act in which the innocent victim is punished with death – family honor takes precedence over individual life. In Titus Andronicus, Rome is already in decline, perhaps decadent, and the Andronici are striving to preserve, imperfectly and nostalgically, older Roman values that are already out of date.”

—————

Here’s the schedule for the next week:

We’ll finish reading Titus this weekend, I’ll post on it Sunday evening/Monday morning.

My Tuesday evening/Wednesday post will be final thoughts on Titus, plus a look at Sonnet #29.

I plan on taking Thanksgiving off – so my next post will be on Sunday evening, November 27, with an introduction (and first assignment) for our next play, Henry VI, Part One.

Enjoy. And enjoy your weekend.

——————————–

And for a weekend “bonus,” and since so much seems to come from it, the Brookes More’ translation of the pertinent section of Book VI of Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

TEREUS AND PHILOMELA

[412] The lords of many cities that were near, now met together and implored their kings to mourn with Pelops those unhappy deeds.—The lords of Argos; Sparta and Mycenae; and Calydon, before it had incurred the hatred of Diana, goddess of the chase; fertile Orchomenus and Corinth, great in wealth of brass; Patrae and fierce Messena; Cleone, small; and Pylus and Troezen, not ruled by Pittheus then,—and also, all the other cities which are shut off by the Isthmus there dividing by its two seas, and all the cities which are seen from there. What seemed most wonderful, of all those towns Athens alone was wanting, for a war had gathered from the distant seas, a host of savage warriors had alarmed her walls, and hindered her from mourning for the dead. Now Tereus, then the mighty king of Thrace, came to the aid of Athens as defense from that fierce horde; and there by his great deeds achieved a glorious fame. Since his descent was boasted from the mighty Gradivus, and he was gifted with enormous wealth, Pandion, king of Athens, gave to him in sacred wedlock his dear daughter, Procne. But Juno, guardian of the sacred rites attended not, nor Hymenaeus, nor the Graces. But the Furies snatched up brands from burning funeral pyres, and brandished them as torches. They prepared the nuptial couch,—a boding owl flew over the bride’s room, and then sat silently upon the roof. With such bad omens Tereus married her, sad Procne, and those omens cast a gloom on all the household till the fateful birth of their first born. All Thrace went wild with joy—and even they, rejoicing, blessed the Gods, when he, the little Itys, saw the light; and they ordained each year their wedding day, and every year the birthday of their child, should be observed with festival and song: so the sad veil of fate conceals from us our future woes.

[438] Now Titan had drawn forth the changing seasons through five autumns, when, in gentle accents, Procne spoke these words: “My dearest husband, if you love me, let me visit my dear sister, or consent that she may come to us and promise her that she may soon return. If you will but permit me to enjoy her company my heart will bless you as I bless the Gods.” At once the monarch ordered his long ships to launch upon the sea; and driven by sail, and hastened by the swiftly sweeping oars, they entered the deep port of Athens, where he made fair landing on the fortified Piraeus. There, when time was opportune to greet his father-in-law and shake his hand, they both exchanged their wishes for good health, and Tereus told the reason why he came. He was relating all his wife’s desire. Promising Philomela’s safe return from a brief visit, when Philomela appeared rich in her costly raiment, yet more rich in charm and beauty, just as if a fair Dryad or Naiad should be so attired, appearing radiant, from dark solitudes. As if someone should kindle whitening corn or the dry leaves, or hay piled in a stack; so Tereus, when he saw the beautiful and blushing virgin, was consumed with love. Her modest beauty was a worthy cause of worthy love; but by his heritage, derived from a debasing clime, his love was base; and fires unholy burned within from his own lawless nature, just as fierce as are the habits of his evil race.

[461] In the wild frenzy of his wicked heart, he thought he would corrupt her trusted maid, her tried attendants, and corrupt even her virtue with large presents: he would waste his kingdom in the effort.—He prepared to seize her at the risk of cruel war. And he would do or dare all things to feed his raging flame.—He could not brook delay. With most impassioned words he begged for her, pretending he gave voice to Procne’s hopes.—his own desire made him wax eloquent, as often as his words exceeded bounds, he pleaded he was uttering Procne’s words. His hypocritic eyes were filled with tears, as though they represented her desire—and, O you Gods above, what devious ways are harbored in the hearts of mortals! Through his villainous desire he gathered praise, and many lauded him for the great love he bore his wife.

[475] And even Philomela desires her own undoing; and with fond embraces nestles to her father, while she pleads for his consent, that she may go to visit her dear sister.—Tereus viewed her pretty pleading, and in his hot heart, imagined he was then embracing her; and as he saw her kiss her father’s lips, her arms around his neck, it seemed that each caress was his; and so his fire increased. He even wished he were her father; though, if it were so, his passion would no less be impious.—Overcome at last by these entreaties, her kind father gave consent. Greatly she joyed and thanked him for her own misfortune. She imagined a success, instead of all the sorrow that would come.

[486] The day declining, little of his toil remained for Phoebus. Now his flaming steeds were beating with their hoofs the downward slope of high Olympus; and the regal feast was set before the guests, and flashing wine was poured in golden vessels, and the feast went merrily, until the satisfied assembly sought in gentle sleep their rest. Not so, the love-hot Tereus, king of Thrace, who, sleepless, imaged in his doting mind the form of Philomela, recalled the shape of her fair hands, and in his memory reviewed her movements. And his flaming heart pictured her beauties yet unseen.—He fed his frenzy on itself, and could not sleep.

[494] Fair broke the day; and now the ancient king, Pandion, took his son-in-law’s right hand to bid farewell; and, as he wept, commended his dear daughter, Philomela, unto his guarding care. “And in your care, my son-in-law, I trust my daughter’s health. Good reason, grounded on my love, compels my sad approval. You have begged for her, and both my daughters have persuaded me. Wherefore, I do entreat you and implore your honor, as I call upon the Gods, that you will ever shield her with the love of a kind father and return her safe, as soon as may be—my last comfort given to bless my doting age. And all delay will agitate and vex my failing heart. And, O my dearest daughter, Philomela, if you have any love for me, return without too long delay and comfort me, lest I may grieve; for it is quite enough that I should suffer while your sister stays away.”

[504] The old king made them promise, and he kissed his daughter, while he wept. Then did he join their hands in pledge of their fidelity, and, as he gave his blessing, cautioned them to kiss his absent daughter and her son for his dear sake. Then as he spoke a last farewell, his trembling voice was filled with sobs. And he could hardly speak;—for a great fear from some vague intuition of his mind, surged over him, and he was left forlorn.

[511] So soon as Philomela was safe aboard the painted ship and as the sailors urged the swiftly gliding keel across the deep and the dim land fast-faded from their view, then Tereus, in exultant humor, thought, “Now all is well, the object of my love sails with me while the sailors ply the oars.” He scarcely could control his barbarous desire—with difficulty stayed his lust, he followed all her actions with hot eyes.—So, when the ravenous bird of Jupiter has caught with crooked talons the poor hare, and dropped it—ruthless,—in his lofty nest, where there is no escape, his cruel eyes gloat on the victim he anticipates.

[519] And now, as Tereus reached his journey’s end, they landed from the travel-wearied ship, safe on the shores of his own kingdom. Then he hastened with the frightened Philomela into most wild and silent solitudes of an old forest; where, concealed among deep thickets a forbidding old house stood: there he immured the pale and trembling maid, who, vainly in her fright, began to call upon her absent sister,—and her tears implored his pity. His obdurate mind could not be softened by such piteous cries; but even while her agonizing screams implored her sister’s and her father’s aid, and while she vainly called upon the Gods, he overmastered her with brutal force.—The poor child trembled as a frightened lamb, which, just delivered from the frothing jaws of a gaunt wolf, dreads every moving twig. She trembled as a timid injured dove, (her feathers dripping with her own life-blood) that dreads the ravening talons of a hawk from which some fortune has delivered her.

[531] But presently, as consciousness returned, she tore her streaming hair and beat her arms, and, stretching forth her hands in frenzied grief, cried out, “Oh, barbarous and brutal wretch! Unnatural monster of abhorrent deeds! Could not my anxious father’s parting words, nor his foreboding tears restrain your lust? Have you no slight regard for your chaste wife, my dearest sister, and are you without all honor, so to spoil virginity now making me invade my sister’s claim, you have befouled the sacred fount of life,—you are a lawless bond of double sin! Oh, this dark punishment was not my due! Come, finish with my murder your black deed, so nothing wicked may remain undone. But oh, if you had only slaughtered me before your criminal embrace befouled my purity, I should have had a shade entirely pure, and free from any stain! Oh, if there is a Majesty in Heaven, and if my ruin has not wrecked the world, then, you shall suffer for this grievous wrong and time shall hasten to avenge my wreck. I shall declare your sin before the world, and publish my own shame to punish you! And if I’m prisoned in the solitudes, my voice will wake the echoes in the wood and move the conscious rocks. Hear me, O Heaven! And let my imprecations rouse the Gods—ah-h-h, if there can be a god in Heaven!”

[549] Her cries aroused the dastard tyrant’s wrath, and frightened him, lest ever his foul deed might shock his kingdom: and, roused at once by rage and guilty fear; he seized her hair, forced her weak arms against her back, and bound them fast with brazen chains, then drew his sword. When she first saw his sword above her head. Flashing and sharp, she wished only for death, and offered her bare throat: but while she screamed, and, struggling, called upon her father’s name, he caught her tongue with pincers, pitiless, and cut it with his sword.—The mangled root still quivered, but the bleeding tongue itself, fell murmuring on the blood-stained floor. As the tail of a slain snake still writhes upon the ground, so did the throbbing tongue; and, while it died, moved up to her, as if to seek her feet.—And, it is said that after this foul crime, the monster violated her again.

[563] And after these vile deeds, that wicked king returned to Procne, who, when she first met her brutal husband, anxiously inquired for tidings of her sister; but with sighs and tears, he told a false tale of her death, and with such woe that all believed it true. Then Procne, full of lamentation, took her royal robe, bordered with purest gold, and putting it away, assumed instead garments of sable mourning; and she built a noble sepulchre, and offered there her pious gifts to an imagined shade;—lamenting the sad death of her who lived.

[571] A year had passed by since that awful date—the sun had coursed the Zodiac’s twelve signs. But what could Philomela hope or do? For like a jail the strong walls of the house were built of massive stone, and guards around prevented flight; and mutilated, she could not communicate with anyone to tell her injuries and tragic woe. But even in despair and utmost grief, there is an ingenuity which gives inventive genius to protect from harm: and now, the grief-distracted Philomela wove in a warp with purple marks and white, a story of the crime; and when ’twas done she gave it to her one attendant there and begged her by appropriate signs to take it secretly to Procne. She took the web, she carried it to Procne, with no thought of words or messages by art conveyed. The wife of that inhuman tyrant took the cloth, and after she unwrapped it saw and understood the mournful record sent. She pondered it in silence and her tongue could find no words to utter her despair;—her grief and frenzy were too great for tears.—In a mad rage her rapid mind counfounded the right and wrong—intent upon revenge.

[587] Since it was now the time of festival, when all the Thracian matrons celebrate the rites of Bacchus—every third year thus—night then was in their secret; and at night the slopes of Rhodope resounded loud with clashing of shrill cymbals. So, at night the frantic queen of Tereus left her home and, clothed according to the well known rites of Bacchus, hurried to the wilderness. Her head was covered with the green vine leaves; and from her left side native deer skin hung; and on her shoulder rested a light spear.—so fashioned, the revengeful Procne rushed through the dark woods, attended by a host of screaming followers, and wild with rage, pretended it was Bacchus urged her forth. At last she reached the lonely building, where her sister, Philomela, was immured; and as she howled and shouted “Ee-woh-ee-e!”, She forced the massive doors; and having seized her sister, instantly concealed her face in ivy leaves, arrayed her in the trappings of Bacchanalian rites. When this was done, they rushed from there, demented, to the house where as the Queen of Tereus, Procne dwelt.

[601] When Philomela knew she had arrived at that accursed house, her countenance, though pale with grief, took on a ghastlier hue: and, wretched in her misery and fright, she shuddered in convulsions.—Procne took the symbols, Bacchanalian, from her then, and as she held her in a strict embrace unveiled her downcast head. But she refused to lift her eyes, and fixing her sad gaze on vacant space, she raised her hand, instead; as if in oath she called upon the Gods to witness truly she had done no wrong, but suffered a disgrace of violence.—Lo, Procne, wild with a consuming rage, cut short her sister’s terror in these words, “This is no time for weeping! awful deeds demand a great revenge—take up the sword, and any weapon fiercer than its edge! My breast is hardened to the worst of crime make haste with me! together let us put this palace to the torch! Come, let us maim, the beastly Tereus with revenging iron, cut out his tongue, and quench his cruel eyes, and hurl and burn him writhing in the flames! Or, shall we pierce him with a grisly blade, and let his black soul issue from deep wounds a thousand.—Slaughter him with every death imagined in the misery of hate!”

[619] While Procne still was raving out such words, Itys, her son, was hastening to his mother; and when she saw him, her revengeful eyes conceiving a dark punishment, she said, “Aha! here comes the image of his father!” She gave no other warning, but prepared to execute a horrible revenge. But when the tender child came up to her, and called her “mother”, put his little arms around her neck, and when he smiled and kissed her often, gracious in his cunning ways,—again the instinct of true motherhood pulsed in her veins, and moved to pity, she began to weep in spite of her resolve. Feeling the tender impulse of her love unnerving her, she turned her eyes from him and looked upon her sister, and from her glanced at her darling boy again. And so, while she was looking at them both, by turns, she said, “Why does the little one prevail with pretty words, while Philomela stands in silence always, with her tongue torn out? She cannot call her sister, whom he calls his mother! Oh, you daughter of Pandion, consider what a wretch your husband is! The wife of such a monster must be flint; compassion in her heart is but a crime.”

[636] No more she hesitated, but as swift as the fierce tigress of the Ganges leaps, seizes the suckling offspring of the hind, and drags it through the forest to its lair; so, Procne seized and dragged the frightened boy to a most lonely section of the house; and there she put him to the cruel sword, while he, aware of his sad fate, stretched forth his little hands, and cried, “Ah, mother,—ah!—” And clung to her—clung to her, while she struck – her fixed eyes, maddened, glaring horribly – struck wildly, lopping off his tender limbs. But Philomela cut through his tender throat. Then they together, mangled his remains, still quivering with the remnant of his life, and boiled a part of him in steaming pots, that bubbled over with the dead child’s blood, and roasted other parts on hissing spits.

[647] And, after all was ready, Procne bade her husband, Tereus, to the loathsome feast, and with a false pretense of sacred rites, according to the custom of her land, by which, but one man may partake of it, she sent the servants from the banquet hall.—Tereus, majestic on his ancient throne high in imagined state, devoured his son, and gorged himself with flesh of his own flesh—and in his rage of gluttony called out for Itys to attend and share the feast! Curst with a joy she could conceal no more, and eager to gloat over his distress, Procne cried out, `Inside yourself, you have the thing that you are asking for!”—Amazed, he looked around and called his son again:– that instant, Philomela sprang forth—her hair disordered, and all stained with blood of murder, unable then to speak, she hurled the head of Itys in his father’s fear-struck face, and more than ever longed for fitting words. The Thracian Tereus overturned the table, and howling, called up from the Stygian pit, the viperous sisters. Tearing at his breast, in miserable efforts to disgorge the half-digested gobbets of his son, he called himself his own child’s sepulchre, and wept the hot tears of a frenzied man. Then with his sword he rushed at the two sisters.

[667] Fleeing from him, they seemed to rise on wings, and it was true, for they had changed to birds. Then Philomela, flitting to the woods, found refuge in the leaves: but Procne flew straight to the sheltering gables of a roof—and always, if you look, you can observe the brand of murder on the swallow’s breast—red feathers from that day. And Tereus, swift in his great agitation, and his will to wreak a fierce revenge, himself is turned into a crested bird. His long, sharp beak is given him instead of a long sword, and so, because his beak is long and sharp, he rightly bears the name of Hoopoe.

The speech by Marcus worked well for me. Especially in the Taymor movie clip, it seemed all part of the weird dreamscape (nightmare!) that the movie portrayed–as though time was suspended in a way. Also, maybe the speech moves the viewer from shock over what has happened….to the next step in the plot. And in the movie clip, Marcus is gathering Lavinia up by the end of the speech. And maybe it made the audience cry about Lavinia? I thought it was moving.

Reading it again, Lavinia was running away from him at the beginning of the speech. “Who is this? My niece, that flies away so fast?” He has to convince/coax her to come to him–more reason for the length of the speech to me.

And rereading Act IV.1, I think that they all know she was raped from the beginning…Titus says, while she is turning the pages to Philomel’s story: “And rape, I fear, was root of thine annoy.”

I think that once they get the names of Chiron and Demetrius–they are then mobilized up for revenge! Maybe that’s what makes it seem like they don’t care beforehand.

I too am finding this play more compelling to read than I thought–i am wondering if the difference is that the back-and-forth word-play/puns are easier to understand–we all know what hands are!

GGG: I’m going to have to read Act IV 1, then, because my immediate impression was that it was the rape that raised the call for vengeance. And as for finding more compelling and easier…I honestly think a part of it (for all of us, because I agree) is that we’re learning HOW to read Shakespeare — we’re becoming more used to his rhythms, the words and prose, and even knowing how to break down the lines and see the wordplay for ourselves.

Maybe I misunderstood. i read it again, and because Marcus mentioned Tereus and Philomel, I assumed he realized she had been raped as well. But maybe Titus didn’t get that until Act IV.

I find the passage of time confusing in this play. Tamora had time to be impregnated and have a baby, but otherwise it seems like it is all happening in a very short time. Did I miss something, or is this is just one of those instances where we’re supposed to suspend disbelief, etc.?

My guess is that there’s a long enough period of time between when Lucius is forced to exile and when he returns at the head of the army of Goths for the birth of Tamora’s son (she may well have been pregnant earlier) to make sense.